This week, Chris is taking a second look at the Minnesota Starvation Experiment. Recently, he came across two papers that followed up on the experiment, and he’s reviewing them today, and chatting about the new information they contain.

00:00:00

00:04:45

00:11:50

00:15:30

00:18:00

00:18:45

00:25:10

00:28:45

00:34:30

00:39:00

00:44:45

00:00:00

Chris Sandel: Welcome to Episode 147 of Real Health Radio. You can find the links talked about as part of this episode at the show notes, which is www.seven-health.com/147.

Over the last handful of weeks, I’ve been starting the podcast by mentioning I’m taking on new clients. This will be the last time you’ll hear me mentioning this for a while because at the time of recording this, I only have one spot left, and then I won’t be starting with new clients again until about the August or September time. Client work is the foundation of my business and the thing I enjoy the most, and after working with clients for the last decade, I feel confident in saying I’m very good at what I do.

When I’ve reflected on all the clients I’ve worked with over the last couple of years, there are a handful of topics that are my area of expertise or specialty areas. One of the biggest is helping women get their periods back, so recovery from hypothalamic amenorrhea or HA. This is often a result of undereating and over-exercising, and it’s almost always coupled with body dissatisfaction or fear of weight gain.

The work with these kinds of clients, as with really all clients, is a mix of understanding physiology and how to support the body, but also being compassionate and understanding the psychology and uncovering the whys behind these clients’ behavior and figuring out how to change this. I’ve recently had one client get her period back after it being absent for 20 years, and then in the same week another client had her first period in 10 years.

I also work to help clients who are disordered eaters or have previously been diagnosed with an eating disorder. With these clients, there are symptoms that are commonly occurring: water retention, poor digestion, always cold, peeing in the night, often waking multiple times in the night, no periods or bad PMS symptoms, low energy, poor sleep, low thyroid. There’s also common mental and emotional symptoms: a compulsion for exercise, fear of certain foods, anxiety, low mood or depression, poor body image and fear of gaining weight.

With these clients, it’s using that same mix of understanding science and compassion to help them recover. I know that full recovery is possible, and I’ve had many clients who’ve had multiple stays at inpatient facilities where nothing worked, and they’ve now got to a place where they are fully recovered.

The final area is helping clients transition out of dieting and how to learn to listen to their body. They’ve had years or decades of dieting, and nothing has worked. They know it’s a failed endeavor, but they’re struggling to figure out how to eat without dieting. How do they listen to their body? What should they eat? They’re confused and overwhelmed. With this work, it’s often a combination of intuitive eating, a non-diet approach, my nutrition understanding, and being able to guide clients towards interoceptive awareness amongst other things that helps them put an end to their dieting habits and truly learn how to nourish their body and take care of themselves.

It’s these kinds of clients that make up the bulk of my practice. I’m very good at helping them get to a place with their food and their body and even with their life that they think is impossible.

If any of these scenarios sound like you and you’d like help, please get in touch. Head over to www.seven-health.com/help, and there you can read about how I work with clients and apply for a free initial chat.

Welcome to Real Health Radio: Health advice that’s more than just about how you look. Here’s your host, Chris Sandel.

Hey, everyone. Welcome back to another episode of Real Health Radio. Thanks for joining me once again. This week, I am doing a solo episode, and it’s one I’m pretty excited about.

00:04:45

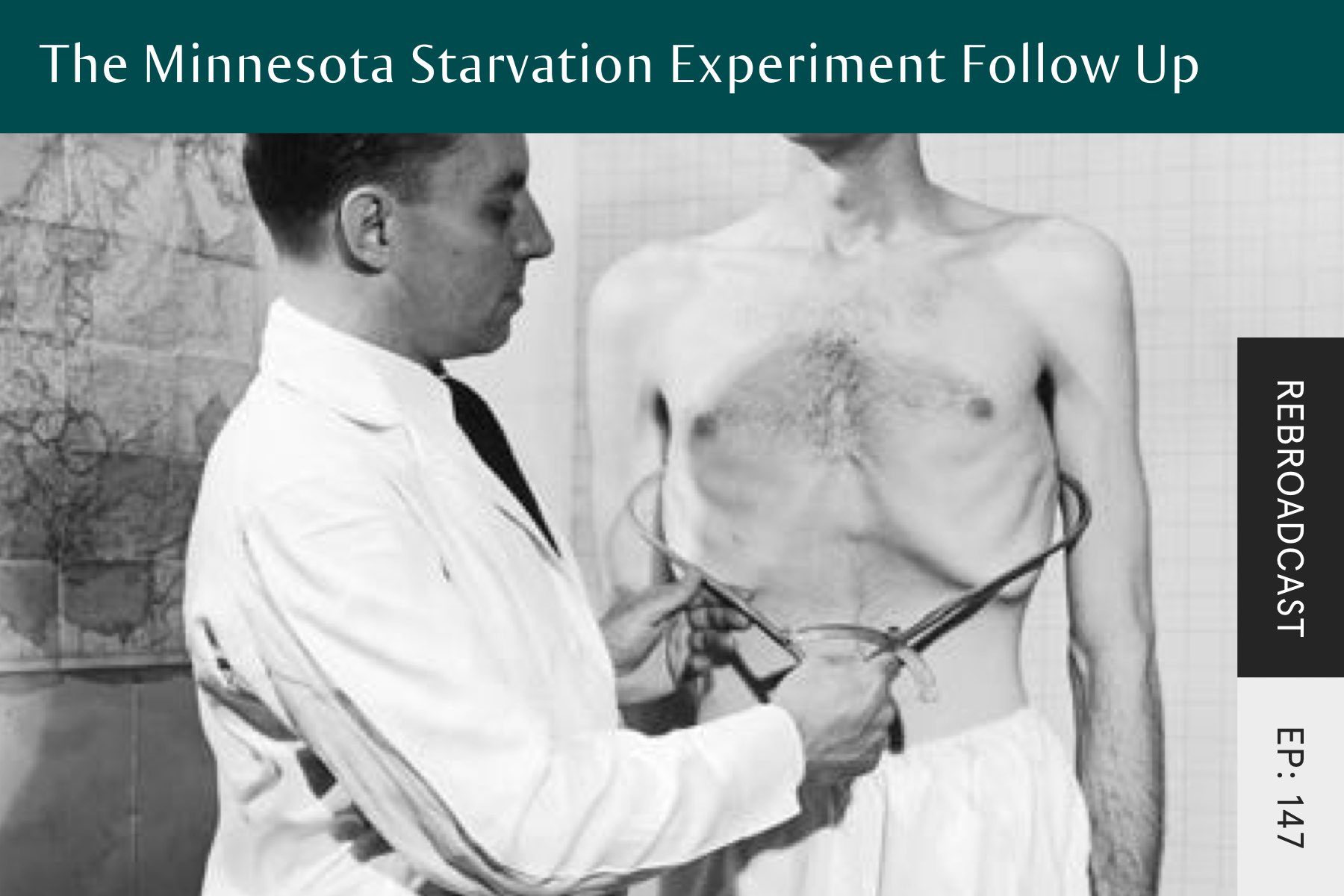

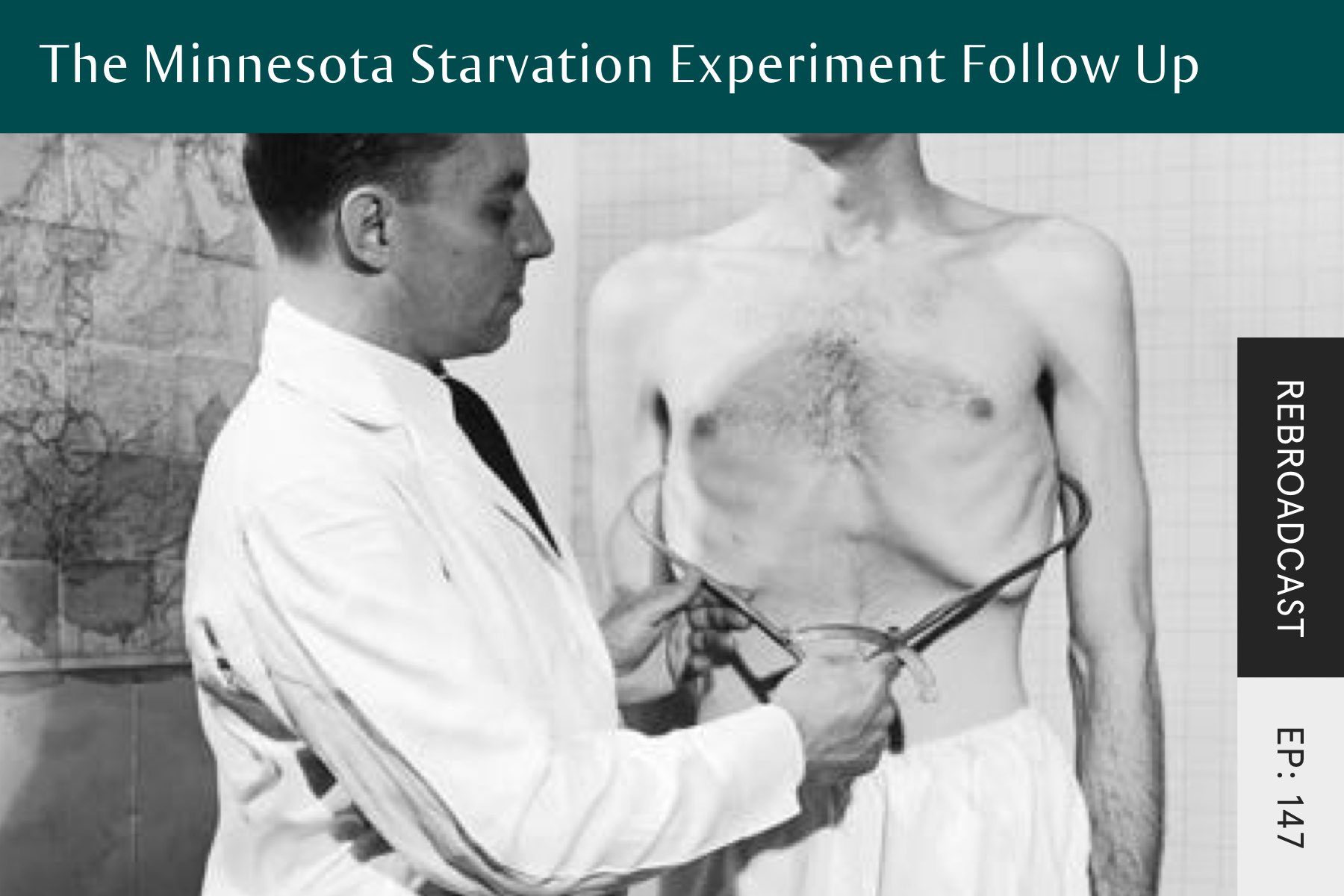

Nearly 3 years ago, I released an episode of the podcast looking at the Minnesota Starvation Experiment. It was Episode 42. This was an experiment that I’d been really fascinated with from as soon as I first heard about. It was done towards the end of the Second World War, and it involved 36 men who were starved on a restricted diet for 6 months while being closely monitored, and then after the restriction ended, they were allowed to eat an unrestricted amount of food and were monitored as part of this recovery.

It’s an experiment that, for ethical reasons, couldn’t be done today, but because of what was done and the level of detail in which everything was recorded, it’s an experiment that has informed so much of what we know about restriction, especially with eating disorders. So to say that it was a seminal piece of research is really an understatement.

In that podcast that I did nearly 3 years ago, I detailed what happened as part of the experiment – the ins and outs of the changes that the men went through in terms of their health as part of the restriction, and not just their physical health, but their mental health and their emotional health and basically how it affected all their areas of life. Then I talked about the rehabilitation and what it looked like, and the weight gain and the pattern that this took and how the men then reached full recovery.

All of this was based on the two-volume monograph called The Biology of Human Starvation that Ancel Keys, who was the lead experimenter, released in 1960.

During that episode, I made a comment that I wonder what became of the men. Keys had followed up with some of the men for about a year after the restriction was over, but that was it.

Recently, I was sent an email by a lovely listener called Suzie, and she said that she’d listened to that episode and that I’d mentioned I didn’t know what happened to the men, so she was now linking me to a study that was done with these men. This study appeared in the Archives of Psychology in March of 2018 and was entitled “A 57-year follow-up investigation and review of the Minnesota study on human starvation and its relevance to eating disorders.”

It was a paper in which 19 of the previous 36 participants were contacted and interviewed about their experience in the study. The men at the stage of being contacted and interviewed were between ages 75 and 83, and the interviews were done in 2002.

It was completely fascinating getting to see how they remembered the experiment and also how some of the details that Keys spoke about in the 1950s, and which I talked about in my podcast, were actually incorrect – information that would be really helpful for people in recovery to hear.

In this paper, towards the end, they actually make reference to another paper in which the participants had been interviewed, and these interviews were done a little later, in 2003 and 2004. I found this paper. It’s called “They starved so that others be better fed: Remembering Ancel Keys and the Minnesota experiment” and appeared in the Journal of Nutrition in 2005. Again, it’s just amazing to be able to read about how these men felt about this experience so many years on.

I decided that I wanted to do an update show to talk about the findings in these two papers. The Minnesota Starvation Experiment, the original episode that I did on this, is one of my most listened-to episodes, and it’s one of the episodes that people most regularly contact me about, mostly to say thank you and how helpful it was to be hearing about the experiment.

There’s a few things that I now want to do with this episode. One is that I want to add in more details about the original experiment that I now know about because I’ve been able to go through these newer papers, so I guess adding a bit more color to what happened in the experiment.

Another goal is to explain what happened after the experiment. In Keys’ work, it seemed that everything was neatly tied up within about a year after, and these extra interviews really show that that wasn’t the case for a lot of the men.

Then the final goal is to talk about where this research is and isn’t so applicable to eating disorders. It’s often held up that what happened in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment is what happens in say anorexia and what happened in recovery is what happens with eating disorder recovery where there’s been restriction. While I would agree with these comments at a general level, there are many differences. This was explored by one of the papers, so I want to talk about it.

What I will say is that while this episode is kind of a standalone show, I would highly recommend going through the first episode as well. That’s Episode 42. I’m not going to cover everything from that original episode, so think of this as more a companion episode. This will make sense on its own, but you’re going to be missing out on a lot of details if you haven’t listened to the other one too. I will put a link to the first podcast in the show notes; I will also put a link to the two papers that I’ve already mentioned that did the interviews with the guys.

The final thing I’ll mention before jumping into this is just to keep in mind that memory is fallible. The interviews with these men were done 57 and then 60 years after the event. Memory isn’t an exact copy of what happened, but it becomes affected by time and emotions and other life events.

During my end-of-year roundup where I talk about my favorite books and documentaries and podcasts, I made reference to two really incredible podcasts that Malcolm Gladwell did in the last season of Revisionist History looking at how bad and inaccurate our memory often is, even with events where we think we would be crystal-clear – asking New Yorkers what they did on the day of September 11, or for someone who is attacked or assaulted. Memories change and become somewhat corrupted.

I’ll link again to both of those podcasts in the show notes if you want to check them out, because I find it really fascinating. I’m not disputing what any of the men said; just that we need to keep in mind that memory might not be as accurate, and if anything, they’ve probably suffered in their memories of the agonies and what they went through as part of the experiment, so maybe looking through it with rose-tinted glasses.

That’s it for the caveats and the disclaimers to keep in mind.

00:11:50

To start with, let me give a very brief overview of what happened as part of the experiment. This won’t go into as much detail as the first episode and might have extra details that I didn’t include in the first episode that I’ve now found out, but giving this overview will bring someone up to speed if they haven’t listened to that first episode – or if you listened to it 3 years ago and can’t really remember it.

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment was conducted between 1944 and 1945. The Second World War had created conditions that meant it was likely that millions in Europe and in Asia could face severe famine, so the experiment really hoped to learn more about how the body reacts to starvation to help create a solution for the likely food shortage that was going to be impending.

As part of the study, there were 36 men. They were all white, ranging from ages 22 to 33. The final 36 men were picked from an original group of 400 men. The inclusion criteria specified they wanted men with good physical and mental health, normal weight range, unmarried, the ability to get along with others under difficult conditions, and a genuine interest in relief and rehabilitation work.

Each participant also completed the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (the MMPI), which had been published in 1943, so just a couple of years before this study. It’s something that is still in use today, although it has been updated over the decades. It’s a psychometric test of personality and psychopathology, asking questions related to anxiety and obsessiveness and depression and anger and self-esteem and a whole host of other areas.

It was a test that was done to screen all of the original candidates, but it was also retested throughout the experiment to see how starvation was affecting their personality and their moods and their thoughts.

During the study, participants were assigned to do various housekeeping and administrative duties within the laboratory. They were allowed to participate in university classes and activities. Many of the men took advantage of this opportunity and did coursework at the University of Minnesota while the experiment was going on. I think a few even completed enough to earn additional degrees during the experiment.

They were also required to walk 22 miles a week, and this could be outside or it could also be on a treadmill, and they had to keep a diary. But aside from that and aside from having to have mealtimes together, and they had to sleep together in a dorm, the subjects didn’t have any restrictions placed on them. They didn’t have any restrictions placed on their social lives.

The study started with 12 weeks of a control period where the men ate approximately 3,200 calories a day. This was to get them to their ideal weight and was really to create calorie balance. This is what they were roughly needing every day on a normal day of eating.

00:15:30

The next 24 weeks was the starvation part of the experiment. The men had their calorie intake cut to approximately 1,560 calories. The diet as part of this was meant to reflect the diet that would be experienced in war-torn areas of Europe, so mostly included potatoes and turnips and rutabagas (also known as swedes), dark bread, and macaroni.

The goal of this 24-week period was for each of the men to lose a minimum of 25% of their body weight, and of the 36 men, 32 of the men reached this goal. Four of them didn’t, and then they were cut from the experiment because they didn’t lose enough weight. This is something that I’ll talk about more in a moment.

There was some extra information I found out from these new papers that I wanted to share that I didn’t cover in the first podcast. During the starvation period, there were two meals per day between Monday through Saturday. They had one meal at 8:00 in the morning; they’d have another meal at 6:00 at night, and then there wouldn’t be any other eating outside of that. On Sundays there was a slightly larger meal that was served at 12:45.

The amount of food that each man received at mealtime depended on how well he was progressing towards the weekly weight loss goals. Usually the reductions or the additions were made in the form of slices of bread. While I said earlier that the intake was reduced to approximately 1,560 calories, it really did depend on the individual.

Let me quote Daniel Peacock, who was one of the participants, talking about this. “Every Friday, late in the day, they would post a list of our names and what our rations would be for the following week – the calories, either minus or plus. Some of us, we’d go off to the movie. In other words, we delayed seeing that list. We dreaded seeing that list for the fear that it was certainly going to be reduced rations. It’s pretty darn certain that it’s going to be bad news because we’re supposed to be descending.”

I said at the start that this experiment is often referred to when talking about eating disorders. Now, obviously this is different to an eating disorder because this starvation is being forced upon these men based upon what the experimenters are dictating, while with an eating disorder it’s more self-imposed.

00:18:00

But how this also differs from an eating disorder, especially something like anorexia, is that the participants dreaded calories going down. They feared it, whereas with anorexia patients, it’s often the opposite. They are drawn to reducing their calories, and each time there’s a reduction, this becomes the new norm and it then becomes more difficult to increase it again.

But this wasn’t the case for the men. The only reason that they were maintaining this reduction was because of the experiment. If they had been offered more food, they would’ve eaten it. So the reduction was in no way self-imposed – so much so that during the experiment, they had to set up a buddy system. After one of the participants broke diet and was excluded from the experiment, a buddy system was then implemented that required the men to travel in twos whenever outside of the laboratory.

00:18:45

But the buddy system wasn’t just about making sure the men weren’t eating outside of mealtimes; it was also for safety reasons. To quote Jasper Garner, another one of the participants: “Before the buddy system, I was in Dayton Department Store downtown trying to go in. It’s got a rotating door. I couldn’t push it. I got stuck. I had to wait for someone to come along.” A fair indication of the lethargy and the weakness that these men started to experience.

Nearly all of the men remembered the walks that they had to take with their buddies to fulfill the weekly 22 miles that was required. Twelve of the men in the interviews recalled the most dreaded Johnson treadmill test, which involved walking on a treadmill until they felt they literally could not continue. Two of the men fell with total exhaustion upon completion of the test.

The men said that they avoided stairs and any extra exertion wherever possible. One man stated, “Exercising was the hardest thing we did.” Another participant, called Max Kampelman, said: “We would look for driveways whenever we got to cross the street so we wouldn’t have to walk one extra step to get from the road to the sidewalk. So we would walk in the gutter for a while, looking for a driveway.”

None of the men interviewed reported periods of increased activity. They all recalled a gradual decrease in strength, in coordination, in endurance. A sense of lethargy was the case for all the men. Again, this is typically different from those with eating disorders, where exercise becomes a compulsion.

If you’ve listened to any of my episodes with guests like Tabitha Farrar or Marya Hornbacher or Anne-Sophie Reinhardt or guests I’ve had on talking about hypothalamic amenorrhea, like Lu Uhrich or some past client interviews, exercise became a compulsion. Clients started exercising and then it just ramped up, and they found it very difficult to stop and even very difficult to stop moving, even outside of exercise.

In Tabitha Farrar’s book, Rehabilitate, Rewire, Recover, she talks about the migration theory with anorexia, and that this could potentially explain the need to move and never wanting to sit down and be still.

None of the men had this be their story or be the case for them as part of this experiment. All of them reported being tired and lethargic and wanting to do as little physically as they were allowed to. This is probably another place where comparing this study to what happens in some eating disorders just doesn’t match up.

The men confirmed that food and eating and thoughts about and preoccupation with food became the earliest and most prominent focus and the main topic of their conversations. Five of the men recalled collecting recipes or cookbooks. Carl Frederick was one of several men who fell into this category, and during the follow-up interview he reported that he owned nearly 100 cookbooks by the time the experiment was over.

To quote Frederick: “I don’t know many other things in my life that I looked forward to being over with any more than this experiment, and it wasn’t so much because of the physical discomfort, but because it made food the most important thing in one’s life. Food became the one, central, and the only thing, really, in one’s life. And life is pretty dull if that’s the only thing. I mean, if you went to a movie, you weren’t particularly interested in the love scenes, but you noticed every time they ate and what they ate.”

Ten of the men reported distress about the waste of food. Again, this is something that probably runs counter to restrictive eating disorders. Seven of the men reported enjoying the vicarious pleasure of watching others eat, while others tried to avoid watching others eat. Some reported dreaming about eating forbidden foods and waking up feeling guilty. During mealtimes, three reported creating odd concoctions with their food, while others added spices or additional water to the soup. Some ate very rapidly while others dawdled over their food and licked their dishes to get every last morsel out of it.

Four men who were interviewed said that they started smoking during the experiment. Another four men recalled subverting their desire for food by developing other habits, such as collecting and even hoarding items that they didn’t particularly need – things like books or trinkets. Hoarding and kleptomania are common symptoms with eating disorders, even for things that have no relation to food.

As part of the follow-up studies, they asked the men about the changes in body perception or body image. Two of the men who were interviewed said they perceived others, including study staff, to be overweight during semi-starvation, and two said that they were unaware of their own emaciated appearance, although they could see that others were getting thin.

Again, this is probably different to what happens in other eating disorders. Body size and shape, both for the individual who is suffering with the eating disorder and with their judgment of others, typically becomes much more heightened. I know for clients, even when they are very thin and are able to see that they are very thin, they are terrified of putting on weight. They have beliefs about others’ bodies as well. But this wasn’t what was happening for the majority of the men in the study – or at least, what they remember.

00:25:10

I talked earlier about the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. This was the test that looks at different aspects of mood and personality. As starvation went on, all participants saw their scores increase for hypochondriasis, depression, and hysteria. This would happen to varying degrees, but this was so common that the triad of changes got labeled as “semi-starvation neurosis.”

Five of the 32 study completers developed symptoms that went beyond that range of semi-starvation neurosis, and they developed serious clinical worsenings during the starvation phase. This was then reflected in their Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory scores.

For example, one participant experienced severe depression and psychological decompensation at the end of the starvation period, and this culminated in him chopping off three of his fingers on his left hand while chopping wood. I think in the first podcast, I said that this resulted in him being excluded for the study. Well, I was wrong on that. He was interviewed as part of this follow-up, and he wasn’t excluded from the study. He actually recovered very quickly after a brief hospitalization and completed the experiment.

Two of the four men who failed to complete the experiment due to dietary violations had to be hospitalized because of severe decompensation and pre-psychotic symptoms. During the first few weeks of semi-starvation, one of these men began to have strange dreams of “eating senile and insane people.” His profile in terms of his different scores started to suggest something similar to schizoaffective psychosis. Things then got worse for him, he became suicidal and violent, and he was then admitted to a psychiatric ward. But he quickly returned to normal after being allowed to eat unrestricted amounts of food.

Another man began to use enormous amounts of chewing gum, between 40 and 60 packs a day. He then started stealing different food items. He began to root around in the garbage bin and actually eat garbage. Since he failed to lose weight, he was then dropped from the experiment at the end of the starvation period, and he then sought psychological help and voluntarily sought admission to a psychiatric ward. His symptoms, again, subsided over a period of weeks and he eventually made a full recovery.

This participant was actually interviewed as part of the follow-up, and he said that he gained about 30 pounds above his control weight after the starvation period by overeating. It took him about a year to return to his normal eating and normal weight, and then he denied any further psychiatric problems and eventually earned a PhD. Again, once normal eating was allowed, his psychiatric problems disappeared.

There were many other changes physically, mentally, and emotionally that occurred during this semi-starvation or starvation period. This is a lot of what my first podcast on this experiment was focused on, so for more information on that, I would suggest listening to that first episode.

00:28:45

Then there was the recovery period. The recovery period started with 12 weeks of restricted rehabilitation. As part of these 12 weeks, the men were split into different groups and given varied diets to try out. The experimenters were then analyzing how different proteins or different supplement regimes helped. This was for them to understand what would be the best rations to then feed the world if mass food shortage ensued.

What came out of this wasn’t actually a lot. Basically, they found that none of the symptoms really improved very much because the calories were so low. To quote Keys on this, who was the study director: “Enough food must be supplied to allow tissues destroyed during starvation to be rebuilt. Our experiments have shown that in an adult man, no appreciable rehabilitation can take place on a diet of 2,000 calories a day. The proper level is more like 4,000 calories daily for some months. The character of rehabilitation diet is important, but unless calories are abundant, then extra proteins, vitamins, and minerals are of little value.”

This is something that I regularly say when working with clients in recovery, because often there are orthorexic tendencies, people who are wanting to recover eating “healthy.” I’m always saying that calories trump everything else. If that isn’t happening, then recovery is not going to work.

The final period of the experiment was then 8 weeks of unrestricted rehabilitation. The men could eat whatever calorie intake and whatever food they wanted. I say unrestricted, but what I found out as part of these follow-up studies was that it wasn’t completely unrestricted.

During the first 2 weeks of unrestricted re-feeding, most participants ate really large amounts of food. It was estimated they were eating somewhere around 10,000-11,000 calories a day. This increased eating concerned the research team.

In fact, it’s completely normal as part of recovery from an eating disorder to have calories go up that high, but the research team really didn’t know this. One of the men who was part of the study, a participant, Henry Scholberg, was taken to hospital to have his stomach pumped. He overate so much that he developed gastric distention and had to be hospitalized.

Many of the men reported vomiting unintentionally because they ate so much. Harold Blickenstaff, another participant, was sick on the bus on the way home from one of his several meals on Day 1 of the unrestricted eating. He said that he found he simply couldn’t “satisfy his craving for food by filling his stomach.”

Seeing all of this in terms of men being sick and a man being taken to the hospital, Keys’ researchers decided to reinstate dietary controls. During weekdays, intake was restricted, but I’m not sure what the actual amounts were. Then on weekends, it was totally unrestricted. This then led to a pattern of “weekend gorging.” The researchers estimated that the men initially ate between 50% and 200% more on weekends.

As part of the study, there was 8 weeks of this unrestricted eating, and then the majority of the participants left and that was it. Twelve of the men remained in the experiment to be monitored for an additional 2 months. Then 21 of the subjects, so 65%, were reevaluated 8 months after the start of rehabilitation, and then eight men or 25% were reevaluated at 1 year.

This is something I want to flag, because this is not how I described it in the first podcast. I was aware that the unrestricted eating was only for 8 weeks as part of the official experiment and then the men went off, but I believed that it was then all the men that were followed after the experiment and checked in at the 8 month part and the 1 year part, not only 65% of them and then 25% of them.

The changes that actually happened and the time for recovery also differs from what I said in the first podcast, and actually to what Keys had originally reported. In the first podcast, I said that after 12 weeks of eating as much as they wanted, body fat matched pre-experiment levels despite weighing less weight than when they started, and by 8 months of unrestricted eating, lean body mass was restored to pre-experiment levels but abdominal fat was 40% higher than when they started. Then by 46 weeks of unrestricted eating, weight and fat percentage had returned basically to pre-experiment levels.

00:34:30

Let me tell you what the participants remember and what was talked about in the follow-up studies. I’m going to quote one of the studies for this.

“Based on the data gathered in the follow-up, changes in weight were more drastic and lasted longer than reported in the Keys study. The mean weight gain exceeding control weights recalled by 16 follow-up participants was 22 pounds, i.e. 114% instead of 110% of control body weight. Most took longer than 58 weeks to return to their control weight. Seven men had problems for 6 months to a year, five had problems for 2 years, one had problems for 3 years, and one had problems that resolved in 4 to 5 years. Three men described minimal problems with abnormal eating or being overweight. Their weight and eating patterns normalized within 6 months. Three men never returned to their control weight.”

I think this is hugely important because in the study and the way it was presented by Keys, and subsequently how I presented it in the last episode, was that it was all resolved within a year for all of the men. I also know on Gwyneth Olwyn’s site, the Eating Disorders Institute site – used to be called My Eating Utopia – she says, “Your entire recovery process may take you into full remission in as little as 3 months or as long as 24 months; 3 months is very, very rare and 18 months is the medium time to remission.”

While I think those in recovery really crave some kind of timeframe and getting some numbers here could potentially give someone some reassurance, it can also be a problem. So many people in recovery feel like they must be doing it wrong because they are 18 months in and they’re still not there, and the guys in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment were supposedly better in under a year, so why aren’t they? Or that the men had stopped gaining weight or returned to their original size in say 46 weeks, but they’re still gaining and it’s been more than a year.

I just want to set the record straight and say that the men didn’t only take a year to recover. Many of them took much longer than this, and they were only restricting for 6 months in comparison to many clients and many other people who’ve struggled for years or decades with an eating disorder. And the men didn’t have the exercise compulsion or the fear of eating or many other facets that so many with an eating disorder have.

So, one, it’s not a fair comparison, and two, time for recovery varies. Just because it’s taking 2 years or 4 years or 7 years, doesn’t mean it’s been done wrong. The more that someone starts to feel that they are broken or that recovery isn’t going to work for them, the more likely they are to pick up their old behaviors. I would really hate for this to be the case, especially if it’s simply because of this erroneous belief about how long it should take.

I just really wanted to say that because I don’t want to give the wrong impression from the first episode on the Minnesota Starvation Experiment and to say that recovery did take a lot longer for a lot of the men than what was originally reported.

Some of the other comments related to the recovery or the unrestricted eating component – many of the men remember feeling a loss of control over eating during the early re-feeding period. Four men stated that they felt like they were eating more or less continuously for a long time. Jasper Garner, one of the participants, described it as “a year-long cavity that needed to be filled.” Six of 19 men, so 32%, reported binge eating. This is defined as eating large amounts of food in a short period of time along with a feeling of loss of control over eating, and this was particularly the case during the initial ref-eeding period when the restrictions were lifted.

Personally, I see it as a problem referring to this kind of eating as a binge. The word “binge” A) has so many negative connotations, but B) this is eating that is in response to starvation. It’s the body being helpful in sending signals to get you to eat so that you can start to repair the damage because you haven’t been receiving enough food.

00:39:00

After a few weeks of the very high caloric intakes of around 10,000 per day, they then seemed to level off at levels between 3,200 and 4,500 calories – although some people needed much more than this.

During rehabilitation, seven men were concerned about the accumulation of fat in their abdomen and their buttocks, and five of these men reported that during or after the rehabilitation phase, they were bothered by how fat they felt. Three months after the start of rehabilitation, one man wrote in his personal notes, “During this week I’ve regained my control weight. However, certainly it is not the same places as the pounds I had on me when I came to Minneapolis. My arms, thighs, buttocks, and midsection all feel fuller than I can ever recall. My face also looks fatter. However, these reactions may be conditioned by what I’m used to seeing during semi-starvation.”

Seven out of 19 who were interviewed, so 36%, were concerned about their weight as part of recovery or during recovery. I don’t know how concerned they were about their weight, how much this impacted upon their life, but I’d also say that this is different with most eating disorder recovery. Body image concerns would be prevalent in most if not all people recovering, particularly as weight is increasing.

The fact that this didn’t affect the majority of the Minnesota participants who were interviewed as part of this follow-up really indicates another area of difference between this experiment and eating disorder recovery.

But I don’t want to minimize what the men went through as part of the recovery. For some of them, the rehabilitation period proved to be the most difficult part of the experiment. Roscoe Hinkle, one of the participants, noted that the rehabilitation period “turned out to be worse for me than anything else. I had troubles because I didn’t really feel that I was going to come back at all.”

During rehabilitation, the scores indicating recovery from depression correlated with calories received. Basically, as calories went up, depression improved – although it wasn’t always completely linear. This is basically the same with all of the scores on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. More food consistently led to better psychology.

Keys also stressed the dramatic effect that starvation had on mental attitude and personality. He really argued that the democracy and nation-building that would be needed wouldn’t be possible in a population that didn’t have access to sufficient food.

The men reported that dizziness, apathy, and lethargy were the first signs of recovery. Those things were the things that improved the quickest. Then the feelings of tiredness, loss of sex drive, and weakness were slower to improve. Robert McCullagh, one of the participants, noted that he could tell he was beginning to recover when his sense of humor finally returned.

Ten of the men indicated that their perceptions and perspectives regarding food were permanently altered by the study experience. I don’t have any more details than this, but this kind of feels like a fairly standard response and doesn’t necessarily indicate anything particularly negative. If I were starved for a period of 6 months and had my food amounts dictated by a lab, I’d imagine that this is something that would change how I saw food forever. So this question doesn’t tell me too much.

Another thing I want to mention is that participants on the whole felt safe during the experiment. They talked about how much they were looked after and were surrounded by scientists and people checking in on them. This is different to someone with an eating disorder. To quote Samuel Legg, who was one of the participants, “The difference between us and the people we were trying to serve: they probably had less food than we did. We were starving under the best possible medical conditions. And most of all, we knew the exact day on which our torture was going to end. None of that was true for the people in Belgium, the Netherlands, or whatever.”

Again, I think this is the difference between this experiment and an eating disorder. These guys were just waiting for the semi-starvation period to be over. They wanted to eat more and get on and get back to their lives. For someone with an eating disorder, this isn’t necessarily the case. Yes, they may want it all to be over and they want to be able to spend their time on more important things, but there’s much more ambivalence. They are the ones who are restricting or who are over-exercising. It’s not being put upon them like it was in this experiment. There are reasons why they have difficulty stopping these behaviors, whereas for the men, the only thing that was stopping them was the study.

00:44:45

The final point I want to make is something I’ve already touched on, but I want to mention it again.

For all of the men as part of this study, there was no lifelong physical, cognitive, or emotional adverse effects, despite the significant suffering that they went through as part of the experiment. All participants ultimately led interesting and productive lives. All men went on to be college graduates. Six attained PhDs and one a Master’s. Six were college professors, four were teachers, two were ministers, one was an architect, a lawyer, an engineer, and a social worker. All felt that they had led useful and interesting lives.

This is important because for someone in the midst of an eating disorder, it can feel so permanent. It can feel like this is who they are, and it can feel like things will never change. But this isn’t the case. This is not the case for the men in this study, but it’s also not the case for so many clients that I work with or so many people I’ve spoken to who have recovered from an eating disorder. With time and with food, the mind and the body repair.

This isn’t to say there can’t be permanent damage, but it is incredible how much the body can and does repair and how resilient it is. No matter how bad the symptoms can be during the eating disorder and during recovery, the body can get back to a place of basically normal functioning with enough food, rest, and time.

I wholeheartedly believe that full recovery is possible – and this doesn’t necessarily mean that people get back to a place as if the eating disorder never happened. Obviously, an experience like this does shape someone’s life and who they are. But when I say full recovery is possible, I mean that someone can return to being a normal eater. They can have a healthy relationship with exercise and with moving their body. They don’t always have to be on guard and worried that they’re going to be relapsing.

That is it for this week’s show. I hope you have enjoyed this addendum to the original episode. If you have, please share it with others that you know or hope may find it helpful.

As I mentioned at the beginning, I’m currently taking on clients and have just one spot left, so if this episode resonated with you at all, please get in contact. You can head over to www.seven-health.com/help, and you can sign up for a free initial chat.

That is it. I will be back next week with another guest interview. Have a lovely week, and I’ll catch you next Thursday.

Thanks for listening to Real Health Radio. If you are interested in more details, you can find them at the Seven Health website. That’s www.seven-health.com.

Thanks so much for joining this week. Have some feedback you’d like to share? Leave a note in the comment section below!

If you enjoyed this episode, please share it using the social media buttons you see on this page.

Also, please leave an honest review for The Real Health Radio Podcast on Apple Podcasts! Ratings and reviews are extremely helpful and greatly appreciated! They do matter in the rankings of the show, and we read each and every one of them.

My father was Harold Blickenstaff who is quoted above. His relationship to food was forever changed by his participation in the experiment. He never left food on his plate in my experience, and there basically wasn’t anything he would refuse to eat. If you would like to talk about any of this, let me know.