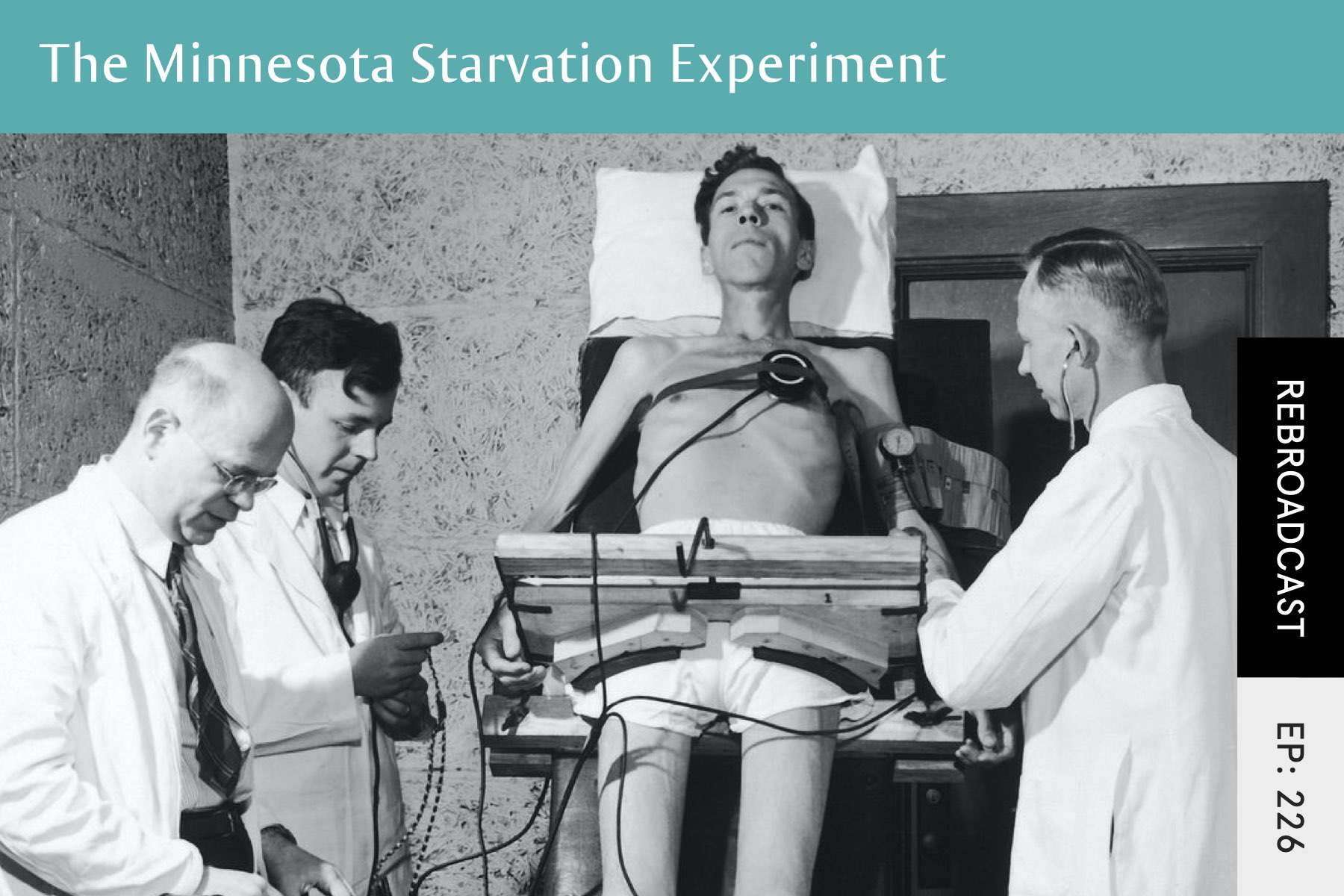

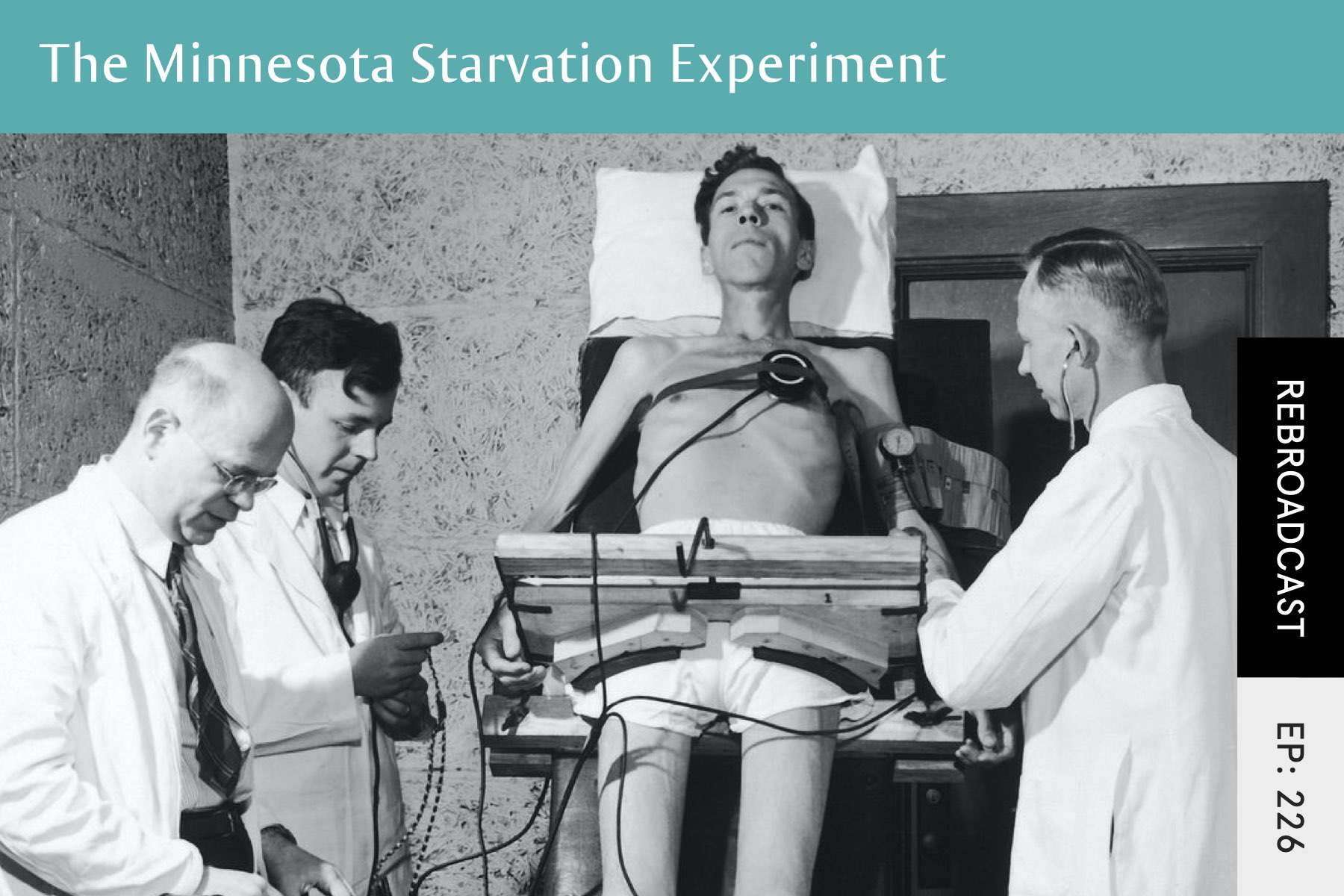

Episode 226: This week on Real Health Radio, I take a deep dive into the Minnesota Starvation Experiment.

As part of the show I cover:

This is actually the third podcast episode I have done on this experiment. The first one looked at the original study, while the second one looked at information contained in two follow up studies done with the men many decades later.

This episode contains much new information (including a re-analysis study of the experiment that only just came out) as well as an update on the information contained in the previous episodes.

This is my definitive guide to the Minnesota Starvation Experiment.

00:00:00

00:01:55

00:06:35

00:13:20

00:15:35

00:18:03

00:22:20

00:32:10

00:39:24

00:41:50

00:47:40

00:52:22

00:56:45

01:00:48

01:13:23

01:16:35

01:22:35

01:24:30

01:30:50

00:00:00

Chris Sandel: Welcome to Episode 226 of Real Health Radio. You can find the show notes and the links talked about as part of this episode at seven-health.com/226.

Just a note before we get started: I’m currently taking on new clients. I specialise in helping clients overcome eating disorders, disordered eating, chronic dieting, body dissatisfaction and negative body image, overexercise and exercise compulsion, and regaining periods. If you’re ready to put an end to these struggles and heal your relationship with food and with body, then please get in contact. You can head over to seven-health.com/help, and there you can read about how I work with clients and apply for a free initial chat. The address, again, is seven-health.com/help, and I’ll also include it in the show notes.

Hey, everyone. Welcome back to another episode of Real Health Radio. I’m your host, Chris Sandel. I am a nutritionist that specialises in recovery from disordered eating and eating disorders and really helping anyone who has a messy relationship with food and body and exercise.

This week I’m back with a solo show. It’s not a completely new episode, but it’s a second edition where I do an update of a previous episode that I’ve done. This one is all about the Minnesota Starvation Experiment. I’ve been a really big fan of this and found this experiment fascinating since I first discovered it. The results of the study and the reading I’ve done because of it have had a real impact on me as a practitioner and in how I think about metabolism and body weight and cravings and food behaviours and a whole host of different things.

00:01:55

I’ve actually done two prior episodes on this experiment before. One was Episode 42, which was released back in June 2016, so over four and a half years ago. Much of the information for that episode came from reading articles that made reference to Ancel Keys’s huge book – it’s a two-volume, 1,385-page opus called The Biology of Human Starvation. This was written after the experiment.

I then released another episode on the topic, and this was Episode 147. With this episode, I’d found some new information. One of the listeners to the show, after listening to my original episode, alerted me to a study that was done with the men many years later. The study appeared in the Archives of Psychology and was entitled ‘A 57-year follow-up investigation and review of the Minnesota study on human starvation and its relevance to eating disorders’. It was a paper in which 19 of the previous 36 participants were contacted and interviewed about their experience in the study. The men at that stage were between 75 and 83 years old, and the interview was done in 2002. It was really fascinating to see how the men remembered the experiment.

In this paper, towards the end of it, it made reference to another paper in which the participants had been interviewed, and these interviews were done a little later, in 2003 and 2004. I found this paper. It’s called ‘They starve so that others be fed: Remembering Ancel Keys and the Minnesota experiment’. It appeared in the Journal of Nutrition in 2005. Again, it was amazing to be able to read how these men felt about this experiment so many years on.

From reading these follow-up papers, I realised that some of the details that Keys spoke about in his book in the 1950’s, which I talked about in my original podcast, were actually incorrect, and it was information that would be really helpful for people in recovery to hear. With Episode 147, I was able to update some of the information, add new insights, and then correct some of the inaccuracies from the first episode.

Then more recently, I read a book by Todd Tucker called The Great Starvation Experiment. This was all about the Minnesota Starvation Experiment. Tucker actually conducted many interviews. He did that with Keys and many of the men who were involved in the studies, and these interviews were done in the early 2000’s. Again, it provided extra insights and new information of things I didn’t know about before.

I’ve also found other papers connected to the study. There’s one in particular that only just came out a matter of months ago that looks at the weight loss and weight gain aspects of the study and explains some of the nuances with it.

What I want to do with today’s episode is really update the two prior episodes and add in all this additional information, so this can be just one solo episode that can be my definitive guide to the experiment.

What I’ll cover as part of the episode is the experiment in detail, looking at how the experiment came to be, the participants, the different phases of the experiment and the symptoms that were experienced by the men as part of the starvation as well as part of the rehabilitation. The experiment is something that is referenced a lot with eating disorders, largely because so many of the issues that arise with an eating disorder are connected to malnutrition and an imbalance of the energy coming in versus what the body needs. Because Keys did such a thorough job of checking so many of these different markers throughout the experiment, it makes it a really fascinating case study.

But at the same time, there is a difference between starvation and an eating disorder. What I want to explore is where the Venn diagram between starvation and eating disorders overlap and where they don’t. That is the plan for this episode. All the papers that I make reference to, you’ll be able to find in the show notes, seven-health.com/226.

00:06:35

Let’s start with an overview. The Minnesota Starvation Experiment was conducted between 1944 and 1945. The Second World War created conditions that meant millions in Europe and in Asia could face severe famine once the war was over. And really, it wasn’t just once the war was over; there were lots of famines going on as part of the war. This included large parts of Europe – the Soviet Union, Poland, Austria, Netherlands. Then there was also India and China and Vietnam and Java in Indonesia. The experiment hoped to learn more about how the body reacted to starvation to create a solution for the impending food shortages, but also the food shortages that were already going on.

At that stage, there had been no proper study of starvation. Despite the fact that famine is very much a regular occurrence as part of mankind, it hadn’t been studied properly. The study was run by Ancel Keys, whose name you may recognise if you’ve spent any time in the health sphere. Keys, many years after the experiment, would go on to study heart disease and cholesterol. It was his research that first made the connection between saturated fat and heart disease, and it’s still being argued about to this day by many in the health community.

Keys had risen to prominence by creating the K-ration for the Army. These were the food rations that were given to many of the soldiers in World War II. Keys worked on the project to find a way of getting the right amount of calories and nutrients into a small box that soldiers could easily carry in their pocket. In this box that weighed I think 28 ounces or 790 grams, it provided the soldiers with 3,200 calories.

With the starvation experiment, Keys was interested in the nutritional requirements for the refeeding of a starving person, but he also wanted to offer insight into how starvation (or, in the case of this experiment, semi-starvation) would ‘change the motivation, then the behavioural consequences of the physical changes, and finally the emotional, intellectual, and social changes which so profoundly influence the personality’.

Given Keys’s background with working with the military, with the K-ration and with other projects, they were in full support of this new experiment. They actually helped him to secure the funding and the participants for it. Keys originally wanted 40 men for the study, and there were over 400 men who applied.

The inclusion criteria specified they wanted good physical and mental health, a normal weight range, to be unmarried, the ability to get along well with others under difficult conditions, and a genuine interest in relief and rehabilitation work. All of these were important, but Keys very much cared about the men getting on with other people, which is an inclination of what he thought was going to be in store for the men.

Each applicant also completed the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), which had just been published in 1943 and is actually still in use today, although it’s been updated over the decades. It’s a psychometric test of personality and psychopathology, and it asks questions linking to anxiety, obsessiveness, depression, anger, self-esteem, and a whole host of other areas. It was a test done at the beginning as a screen for the original candidates, but it was also retested throughout the experiment to see how starvation was affecting personality and mood and thoughts.

Of the original 400 applicants, at the end there were only 36 who stood up to the original screenings and the MMPI.

This experiment, as I said, started in 1944, when World War II was going on. The US had entered the war after the bombing of Pearl Harbour, which was in December of 1941, and this led to military conscription. It required that all men between the ages of 18 and 64 would register. As part of registration, you could fill out a form to say you were a pacifist or a conscientious objector. For those who had this stance and had it approved by their local area who dealt with this, they then became part of the Civilian Public Service (CPS).

During the war, those who were in the CPS were put to work. They did things like soil conservation and forestry and firefighting and agriculture and working in mental institutions. Most of the men who were in the CPS were there because of pacifism related to religious beliefs, and that was true for all the men in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment.

All the men of the CPS were unpaid, which is actually one of the reasons why this experiment was able to happen. To be able to have healthy men be volunteers as part of a study that was going to last the best part of a year, who were then going to be starved and all the while not being paid for it – those conditions don’t come around very often. That’s one of the reasons why this was actually able to happen.

As a side note, this wasn’t the only experiment that men from the CPS were involved in during the war. Most of them were pretty horrible. They would infect men with malaria and then give them experimental treatments. They had the men wear garments infected with lice carrying typhus. They’d have the men swallow nose and throat washings, human waste, and then drinking water that were all contaminated with hepatitis. Some men had to drink seawater and nothing else, and they wanted to see how long they would survive. So the men at CPS were used in a wide range of studies during the war, and none of them sound pleasant.

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment, as the name would suggest, was done in Minnesota. Keys had actually set up his lab underneath a local football stadium in Minnesota, which wasn’t in use during the war. This was where all the men would sleep, which they did together in a big dorm room.

00:13:20

In terms of the 36 subjects, they were all white males and they ranged from 22 to 33 years old. They weighed on average 152.7 pounds, or 69 kilos. The heaviest was 183.9 pounds or 83 kilos, and the lightest was 136.4 pounds or 62 kilos. Body fat percentage at the start of the experiment was also in a range. At the low end, it was 6%. At the high end, it was 25%.

I should mention here that body fat percentage for men and women is different. If you’re a woman and used to thinking about body fat percentage ranges for a woman, these ranges are different.

Each volunteer was assigned a job that would take up about 15 hours of their week. They were required to walk 22 miles a week, and they had to keep a journal about all their thoughts and mood, etc. But aside from mealtimes, having to sleep in a dorm, and having to be the subject of lots of tests throughout the experiment, there were no restrictions placed on the men’s social lives. (I will say that that did change, but I will get to that at some point.)

One of the subjects continued his law studies. He transferred from NYU to Minnesota University. Another one of the men was in a play. Keys scheduled 25 hours a week of instruction classes in language, sociology, and political sciences. As part of the experiment and one of the things used to lure the men into saying that they wanted to be subjects was that they were promised relief training as part of it. Many of the men wanted to still serve their country in some way, and they envisaged once the war was over, they were going to go off overseas and be offering relief work. So this was what that training was meant to be about. Keys also arranged for different speakers to come to the experiment – people that he thought the men would be interested in hearing from.

That is the basic overview.

00:15:35

The study started on the 19th of November, 1944 with 12 weeks of a control period. The goal of this phase was to study the men at this point where they were healthy to get an understanding of where they were at in terms of baseline before starvation commenced.

They also wanted the men’s weight to be stable at this time and to figure out what the men needed. So rather than everyone getting the exact same amount of food, each subject was treated differently. They wanted to see what each individual needed to be weight steady and in energy balance. During this time, the men ate three meals a day, totalling approximately 3,200 calories. On average, that was what they needed to be weight steady, but as I said, it varied from man to man.

Throughout the experiment, Keys and his team measured many different aspects of the men’s mental and physical health which, when we get to he symptoms part, becomes very apparent. Keys really was trying to track absolutely everything.

During this control phase, Keys and his team were figuring out the baselines of all of those. What was someone’s pulse? What was their metabolic rate? What was their sperm count?, etc.

One test that the men had to do was the Harvard fitness test, which was completed on a treadmill. They had to walk for 20 minutes at a pace of 3.5 miles an hour, and then this was doubled to 7 miles an hour. At that point they had to start running and they had to run for 5 minutes or until they fell down. The men did this for the first time very close to the end of the control period. It would actually become something of a source of dread, as the subjects had to do it multiple times during the experiment as they were getting more and more impacted on by starvation.

The control phase was also when the men got to know each other. They were going to spend a lot of time together, and while they were well fed and in high spirits to start with, they could bond and hang out.

During this control phase, the men really enjoyed themselves. In comparison to their previous CPS jobs that they’d just come from, like working in a poorly funded mental institution or being stranded in a forest in the middle of nowhere chopping down trees, the control phase was like a pleasant holiday. They were well fed with lots of delicious food and got to chat and hang out with guys who had similar beliefs.

00:18:03

But all of that changed on the 12th of February, 1945, when they entered the starvation, or as it was called, the semi-starvation phase. This phase would last 24 weeks.

Keys wanted to emulate what had happened in many of the famines that had been occurring during the war where overnight, an area was taken over by an enemy and then food intake was instantly reduced. So overnight, the calories were cut in half to approximately 1,560 calories. The diet they were eating as part of this was meant to reflect the diet experienced in war-torn areas of Europe, so mostly included potatoes, turnips, rutabagas or swedes, dark bread, and macaroni.

During the starvation period, two meals were served Monday through Sunday – one around 8:00 or 8:30 a.m. and one around 5:30 or 6:00 p.m. There were three different days on rotation, and on those different days they would have the same meals and it would rotate.

With each participant, they actually received slightly different amounts of calories. Keys set up individual weight loss goals for each of the subjects and what he wanted them to lose as part of the experiment. These ranged from between 19% and 28%, and it took into account the participant’s age and body weight and body type and relative body fat percentage at the start of the experiment. He constructed a predicted weight loss curve. The amounts the subjects received each week were based on how they were doing with following this prediction. Usually the reductions or additions, but most normally reductions, were made in the form of slices of bread or potatoes. So while I said that the intake was approximately 1,560 calories, it really depended on each individual’s weight loss.

Let me quote Daniel Peacock, who was one of the participants, talking about this: ‘Every Friday late in the day, they would post a list of all our names and what our rations would be for the following week, the calories, either plus or minus. Some of us, we’d go off to the movie. In other words, we delayed seeing that list; we dreaded seeing that list for fear that it was certainly going to reduce our rations. It’s pretty darn certain that’s going to be bad news because we’re supposed to be descending’.

Two of the subjects, James Plaugher and Bob Wiloughby, were the biggest guys in the experiment, and they lost weight the slowest. Keys was suspicious that they were cheating. Because they were losing weight slower than the intended curve, after a couple of weeks they had the lowest calories of anyone, and they were on around 1,100-1,200 calories instead of the average, 1,570. When weight continued to not drop quickly enough for both the men, they were dropped down to less than 1,000 calories a day.

Something interesting that I found out from the Ted Tucker book was that the man actually had a relief meal at the end of the 15th week. It was 2,366 calories (really nice and specific of Keys). So they had their normal breakfast and then this meal was served in the evening. The participants got to vote on what should be included as part of this relief meal, and it was all the things that they had been dreaming about – bacon, eggs, bread with butter and honey, a chicken roast with gravy and all the trimmings, lots of fruit, peanut butter. At the end of the meal, absolutely nothing was left. The men even ate the peel from the oranges, which really annoyed Keys as he hadn’t calculated and factored this into the meal, which again demonstrates how meticulous he was being with the whole experiment.

At the end of the semi-starvation phase, the average weight lost during the 24 weeks was 16.5 kilos or 37 pounds. This weight loss and the subsequent weight regain as part of the rehabilitation is something I’m going to explore in more detail shortly.

00:22:20

First I want to go through all the symptoms that occurred because of the starvation. As you listen, if you are someone who has a history of dieting or disordered eating or an eating disorder, see how many of these symptoms match up to your own. It won’t necessarily be that all of them will be there, but many will likely be there.

I know that there is also a tendency for those with an eating disorder to find all the reasons that they aren’t sick enough or why it’s not really so bad, so if you are in this place, rather than focusing on the symptoms from the list that don’t occur to you, which ‘proves’ that nothing’s wrong, instead just make a note of how many symptoms actually do occur.

Starting with physical symptoms, decreased pulse. During the control period, the average heart rate was 55 beats per minute. This then dropped down to an average of 35 beats per minute. The lowest was 28 beats per minute. The men’s hearts shrunk by an average of 17%. Their blood volume dropped by 10%. They had low blood pressure and regular dizziness on standing and vertigo. Some even experienced momentary blackouts.

Their basal metabolic rates plummeted and fell by as much as 50%. They had to take pillows with them so that it didn’t hurt so much when they would sit down.

They had an increased sensitivity to cold. All the men wore heavier clothes, more layers. They wanted hot baths and showers. They had freezing cold hands and feet and skin in general, and their lips and fingernails turned blue. Taking a warm shower was one of the highlights of the day. It was the only time where they felt really warm, and the warm water also took away a lot of the physical aches and pains that they felt.

Their tolerance to heat also increased. For example, the men could hold really hot plates in their hands without discomfort. They asked for their food and their coffee and tea to be served unusually hot. Tea and coffee intake increased, and the satisfaction that the subjects got from these drinks also markedly increased. When some of the men had their intake hit 15 cups a day, as part of the experiment they set a 9-cups-a-day limit.

They guzzled water, trying to seek fullness. Some took up smoking to stave off hunger; others chewed gum. A couple of guys chewed up to 40 packs of gum a day until the laboratory set a maximum of two packets a day. They developed a strong craving for salt.

They became obsessed with food. It became the principal topic of conversation and their thoughts. They read books about it – cookbooks, menus. Information on food production became intensively interesting to many of the men who had previously had little or no interest in diet or agriculture. A few even planned to become cooks and open restaurants when this was over. As part of the follow-up interviews, five of the men recalled collecting recipes or cookbooks.

Carl Frederick was one of the several men who fell into this category, and he reported owning nearly 100 cookbooks by the time the experiment was over. To quote Frederick: ‘I don’t know many other things in my life that I looked forward to being over more than this experiment, and it wasn’t so much because of the physical discomfort, but because it made food the most important thing in one’s life. Food became the central and only thing, really, in one’s life. And life is pretty dull if that’s the only thing. I mean, if you went to a movie, you weren’t particularly interested in the love scenes, but you noticed every time they ate and what they ate’.

Plate licking was commonplace as the men sought out ways to extend mealtime or feel fuller. They diluted potatoes with water. They held food in their mouths for a long time without swallowing. They ate in bizarre rituals to try and extend eating time or laboured over combining food together on their plate. One subject wrote, ‘They would coddle their food like a baby or handle it and look over it like it was some gold. They played with it like kids making mudpies’.

During mealtime, some of the men created odd concoctions with their food while others added spices or additional water to their soup. Some ate more rapidly. Some really dawdled over it. Some of the men tried to subvert their desire for food by developing other habits such as collecting and even hoarding items that they didn’t particularly need, so books or trinkets.

The men felt like less physical exercise and spent as much time lying around and trying to keep warm as they could. The men avoided stairs and extra exertion whenever possible. One man stated, ‘Exercising was the hardest thing we did’. Another participant, Max Kampelman, said: ‘We would look for driveways when we got to cross a street so we wouldn’t have to walk up one step to get from the road to the sidewalk. And so we would walk in the gutter for a while, looking for a driveway’.

Some commented that they would become angered if they saw someone running up stairs or doing things that were strenuous. There was a loss of strength. For example, there was a 21% reduction in their strength measured with a back-lift dynamometer, which was one of Keys’s experiments. I mentioned the Harvard fitness test earlier and how they did it at multiple points throughout the experiment. They did this on the last day of the experiment, with the average being a 72% drop in fitness. Most of the men struggled just to walk for 20 minutes at the 3.5 miles an hour pace, and when they increased to the 7 miles an hour pace, they lasted a matter of seconds before falling over and having to be caught by some of Keys’s assistants who were standing on either side of the treadmill.

The men had a decreased interest in sex, with less frequent erections. As time went on, the men’s desire became completely non-existent. And this wasn’t just about desire, but it also then affected their reproductive abilities. For example, sperm samples were taken during the final week of the starvation section and also at the 20 weeks of refeeding. During the last week of starvation the sperm was motile for about 4.8 hours; after 20 weeks of refeeding, it was motile for 25.5 hours.

Obviously, there were no females as part of the experiment, but the female equivalent to this would be anovulatory cycles, so periods where you didn’t ovulate, or hypothalamic amenorrhea, where menstruation completely ceases.

The men had decreased amounts of red blood cells, which are the ones that carry oxygen around the body. They developed certain types of anaemia. Certain white blood cells were also decreased by up to 30%. White blood cells are your immune system.

The men developed oedema, or water retention, and this was particularly in the legs and feet. For some, this was to such a degree that it stalled weight loss and made it difficult for them to predict what their real weights were and what their rations should be cut to.

Hair grew slowly and fell out prematurely. Their nails slowed and stopped growing. Their skin became rough and thin. There was this hardening of the hair follicles, which is called follicular hyperkeratosis, and large parts of their body were covered in permanent goosebumps. So the men prematurely aged in terms of their appearance.

They experienced frequent urination, day and night. Urination in the control phase averaged 1.33 quarts of urine a day, which is around 1.2 litres. It peaked during restriction at 2.58 quarts, which is nearly 2.5 litres. So it more than doubled, and that is part of where the body is at, but also because the men were drinking so much fluids.

The men experienced constipation and digestive issues. The men went from going at least once a day during the control phase to going once or twice a week during starvation.

Cuts and bruises were slow to heal. Muscle cramps and muscle pain were common. They developed dark patches around their eyes. Sleep became interrupted; they weren’t able to sleep through the night. The corneas of the eyes became completely white. The experimenters even tried to reduce redness. They’d get soap and try to induce redness in the men’s eyes, but it just didn’t happen. So what could be easily thought about as healthy and clear eyes are actually a sign of starvation.

Interestingly, the men had improved hearing. Keys theorised that this was because of a lower production of earwax and an enlargement of the auditory canal as the ear tissue shrank, but this also resulted in many of the men having ringing in their ears and was also connected to an increased irritation because of hearing more background noise.

00:32:10

I talked earlier about the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (the MMPI). This was the test that looked at different aspects of mood and personality. As starvation went on, all participants saw their scores increase for hypochondriasis, depression, and hysteria. This was to varying degrees, but it was so common that this triad of changes got labelled as ‘semi-starvation neurosis’.

Five of the 32 study completers developed symptoms that went beyond the range of semi-starvation neurosis. They developed desirous clinical worsening during the starvation phase, and this was reflected in their MMPI scores. For two of these subjects, the response to distress was particularly violent and bordered in psychosis.

For example, one participant experienced severe depression and psychological decompensation at the end of the starvation period, and this even went into the early stages of the restricted rehabilitation. I’ll talk in more detail shortly about what restricted rehabilitation and that phase looked like, but for this subject, he was receiving only an extra 400 calories compared to during the starvation phase. This then culminated in him chopping off three of his fingers on his left hand with an axe while chopping wood. The week before this, he had dropped a car on his hand, but he pulled his hand away at the last moment and it only crushed the very end of his finger.

To give you a perspective on his mental state in respect to the cutting off of three fingers with an axe, he was later quoted as saying, ‘I admit to being crazy mixed-up at the time. I’m not ready to say I did it on purpose. I’m not ready to say I didn’t’. He actually recovered quickly after the injury and a brief hospitalisation and was able to complete the experiment, and he pleaded with Keys to keep him in. He said, ‘For the rest of my life, people are going to ask me what I did during the war, and this experiment is my chance to give an honourable answer to that question’. But this was a change of heart, because his intention with the dropping of the car on his hand and the chopping off the fingers was to get out of the experiment. Then when he was lying in the hospital bed, he changed his mind.

Other mental and emotional changes were loss of ambition and increased depression. They spent more and more time alone, and this was even true for those who were extroverts. There were increased amounts of irritability. There was impaired concentration, judgment, comprehension, and decision-making, increased rigidity and obsessional thinking, reduced alertness, loss of sense of humour, feelings of social inadequacy, neglect of personal hygiene. The men became reluctant to plan activities, to make decisions, to participate in group activities.

I mentioned at the start that Keys offered relief training for the men, and this wasn’t done by Keys personally, but by some of the people at the university and even by some of the men in the group. One of the men spoke French, so he was teaching the others how to speak French. Well, as time went on, the men just stopped caring about this and stopped caring about their relief training and didn’t really go.

Same thing for the speakers that Keys arranged to come. The men would sit and listen, but they were vacant and lifeless and uninterested – the exception being if that person said anything about food, this would be when the subjects would become interested.

The men became less interested in what was going on with the war. Even when the Germans surrendered, not one of the men mentioned it in their journal that day. This was in stark contrast to when they started the experiment and they were all intently following what was going on. Many of the men had parents or relatives who were in parts of Europe, who were in India, so news about the war was really important to know what was happening with their families. But as starvation took hold, this caring about the war and world events was much less important to the men.

Sticking to the restricted eating became more and more difficult, especially when the men were in town or places where food was available. A buddy system was then brought in during Week 9 after one of the subjects admitted to cheating food. That meant that any time the men left the stadium, they had to do so in pairs.

The buddy system wasn’t just about making sure the men weren’t eating outside of mealtimes; it was also for safety reasons. To quote Jasper Garner, who was one of the participants: ‘Before the buddy system, I was in Dayton Department Store downtown, going to go in. It’s got a rotating door. I couldn’t push it. I got stuck. I had to wait until somebody came along’. A fair indication of the lethargy and the weakness that the men experienced.

Some of the men reported distress about the waste of food. There’s a story in the Todd Tucker book about two subjects. They watched a lady eat a meal at a restaurant. She had her main and she left part of that main, and they just couldn’t understand it. She then ate a small part of her dessert and left the rest of it. When she left the restaurant, one of the subjects ran after her and shouted at her for wasting food.

Some of the men really didn’t want to see other people eating food and avoided watching it, but some of the men did take vicarious pleasure in watching other people eat. Some reported dreaming about eating forbidden foods and waking up feeling guilty from that. There were also those who dreamt about cannibalism.

As part of the follow-up studies, they asked about changes in body perception or body image. Two of the men interviewed said that they perceived others, including study staff, to be overweight during the semi-starvation period. Two said that they were unaware of their own emaciated appearance, although they could see the others getting thin.

Here is a great quote from one of the participants that really sums everything up: ‘I’m cold, I’m weak, and now I have oedema [water retention]. Social graces, interests, spontaneous activity, and responsibility take second place to concerns of food. I don’t like to sit near guests, for then it is necessary to entertain and talk with them. I am one of the three or four who still go out with girls. I fell in love with a girl during the control period, but I see her only occasionally now. It’s almost too much trouble to see her, even if she visits me at the lab. It requires effort to hold her hand. Entertainment must be tame. If we see a show, the most interesting part of it is contained in scenes where people are eating. I couldn’t laugh at the funniest picture in the world, and love scenes are completely dull’.

Those are the symptoms that occurred during the experiment.

00:39:24

As a slight tangent, one of the topics that Todd Tucker talks about in the book is he explores other famines throughout history – instances where people were eating even less than the men had in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment and where it went on for much longer than 24 weeks and with no end in sight, not in some nice laboratory, being looked after and monitored and knowing the end point.

I just want to mention one of these, just to show the extremes that the human body goes to to find food.

One such famine is the hunger winter in Leningrad, which started in 1941. Hitler’s army surrounded the city of Leningrad on the 8th of September, 1941 and cut off supplies and all food. The siege ended up lasting 872 days. What did the people do for food? The government gave manual workers 700 calories a day and non-manual workers 473 calories a day. Children were given 423 calories. But as you’d expect, that really pales in comparison to the actual needs of the people.

First they ate all the animals at the zoo. Then they ate all their household pets. Wallpaper was removed, as someone remembered that the paste that’s used to stick wallpaper to the wall was made of potatoes, so the paste was then cooked up to be eaten. Leather was then boiled into this gelatinous mess and eaten.

When this wasn’t enough, people started eating corpses. Children also started to disappear. People turned to cannibalism to survive. In one case, the bones of several children were found inside the apartment of a concert violinist, and a special police force was even set up to combat cannibalism. Some people cut off parts of their own body to eat and to stave off the hunger, which points to both the hunger and the psychosis that ensues because of starvation.

I know this is a fairly bleak demonstration of what hunger can do to us, but I just wanted to mention it because I think it’s important to see what the body will do to actually find food and what can happen when starvation is moved out of a laboratory setting and into a real-life famine.

00:41:50

I said that there were 36 subjects as part of the study. In the end, only 32 were included in the final write-up and evaluation. I want to go through the four subjects that were removed and why.

The first was a subject called Watkins. He struggled from Day 1 of starvation. During the first weeks of the semi-starvation, he began to have strange dreams of ‘eating senile and insane people’. He started buying food in town when he wasn’t allowed, and Keys found out and had his money confiscated. He then started stealing food. Again, Keys found out, so he was then restricted to not leave the stadium. He continued to get worse, and his MMPI profile was similar to a patient being diagnosed with schizoaffective psychosis. All this happened before the halfway mark of the experiment.

I said that there was a buddy system that was brought in because of concerns about cheating, and this happened during Week 9; this was because of Watkins. Three days after the buddy system was introduced, Watkins had an angry outburst at Keys and said that he was going to kill himself and kill Keys. So he was removed from the experiment. He was taken to the psychiatric ward, and within a short number of days of normal eating, his psychosis disappeared and he was released and back to his usual self.

Keys was completely unsympathetic to the plight of Watkins as well as the others who were removed as part of the study. He wrote of Watkins, ‘This subject is a bisexual with poor personality integration and weak self-control’.

The next subject to be removed was Weygandt. During the early part of the experiment, he worked in a grocery store, but he started having mental blackouts where he’d awake and realise he was eating. He’d eat food that the store had marked to be thrown out. Keys found out about this and he was then being heavily watched. Weygandt felt immense shame because of this. Once the buddy system was introduced, he had to give his job up at the store, and his mental state deteriorated pretty sharply because of it.

But in the end, it wasn’t the eating unsanctioned food or his mental health that caused him to be removed. He noticed his urine, despite previously being clear, was now ice tea coloured. Eventually he realised he was peeing blood. He mentioned it to Keys and was dropped out of the experiment during the 18th week of starvation. Within a couple of days of regular eating, the blood in the urine stopped, and within a fairly short time, he was feeling much better. He actually stayed on and helped out in the kitchen until the experiment was over.

There was a quote from one of the researchers, and I’m not sure if he was referring to Watkins or Weygandt here, but he said (and this is talking about when they ate food in town that they shouldn’t be): ‘He kidded with the fountain girls, thought the lights were more beautiful than ever, felt that the world was a very happy place. Then this denigrated into a period of extreme pessimism and remorse. He felt he had nothing to live for, that he’d failed miserably to keep his commitment to staying on reduced rations’.

This feeling of shame and feeling like a failure was true of all the men who were unable to keep up the restricted meals on offer.

The next person to be removed was Plaugher. He admitted to cheating and eating food, but this admission didn’t happen until right at the end. So he actually completed the full starvation phase. Plaugher ate food he’d found on the ground. He ate food found in the garbage. Once expelled from the experiment, he checked himself into the psychiatric ward.

Keys wrote of him, ‘In summary, this subject’s latent personality weaknesses have amplified and been brought to the surface by the stress. He did not have the strength to carry on the programme or the capacity to decide unequivocally to get out of the unpleasant situation. Thus, he developed an experimentally induced neurosis characterised by such symptoms as indecisiveness, self-deprecation, feelings of guilt, restlessness, nervous tension, compulsive chewing gum, and eating off-diet’.

This participant was actually interviewed as part of the 57-year follow-up. He said that he gained about 30 pounds above his control weight after the starvation period. It took him about a year to return to normal eating and normal weight, and he denied any further psychiatric problems and eventually earned a PhD. Again, once normal eating was allowed, his psychiatric problems disappeared.

The final subject to be expelled was Wiloughby. He, along with Plaugher, had the highest weight to start with. These were the two guys that I said were reduced to the lowest amount of calories. The two of them actually got on well and were buddies during the experiment and the whole time. Because their weights weren’t decreasing as expected, they had the most difficult time during the starvation phase in terms of their calories.

After Plaugher confessed to eating outside of the experiment and was expelled, Keys then interviewed Wiloughby about the cheating. Wiloughby categorically denied it. He never confessed, and he was adamant that he hadn’t, but Keys didn’t believe him, so his data was not used as part of the final write-up.

00:47:40

After the starvation phase, there was then the restricted rehabilitation phase, which lasted 12 weeks. The men didn’t actually know what was going to happen during the restricted rehabilitation phase. Most didn’t realise they would still be restricted.

The men were split into four groups, and each group received either 400, 800, 1,200, or 1,600 more calories than during the starvation phase. Then they were further subdivided into groups where some would receive different proteins and vitamins and mineral supplements. It was meant to be a secret about which group everyone was in. The subjects tried to figure it out by watching how much other people were served. No one felt that they were in the highest group, and most felt that they were in the lowest group.

Interestingly, many of the men began to lose further weight in the rehabilitation stage – even men who’d been weight steady. This was because with the extra eating, it reduced the oedema, which reduced their weight.

At 5 weeks of rehabilitation, recovery was still much lower than expected, although recovery was proportional to which group someone was in. The more calories someone received, the quicker they were recovering, but none were making any meaningful recovery compared to what Keys had expected.

So, at 5 weeks, they had another relief meal. This was similar to the one that I mentioned at the 15th week of the experiment. Keys also realised at that point that keeping the men on their current restrictive rehabilitation wasn’t working. They weren’t recovering as he’d hoped, and there was no point leaving them at this level for the entirety of the 12 weeks.

The day after that relief meal, calories were increased across the board by a further 800, meaning that from 5 weeks onwards, the groups were then 1,200, 1,600, 2,000, or 2,400 more calories than during the starvation phase. If we’re then using the 1,560 as the baseline calories that the men were on during the semi-starvation phase, this means that the four groups received roughly 2,760, 3,160, 3,560, or 3,960 if they were in the highest group.

With this change, finally weight started to increase, and so did moods. Again, this was proportionately connected to the number of calories that one was receiving.

Three days after the increase in calories, the men asked for the buddy system to be stopped so that they could go off on their own. Keys and other members of the experiment only agreed because they thought they were going to have a mutiny on their hands, but they actually saw it as a positive because it showed that the men were in higher spirits and were caring. In connection to this, one of the psychologists who was there said, ‘Hungry people mindlessly follow orders. You feed them enough and right away they demand self-government’.

At the end of the 12 weeks of restricted rehabilitation, weight had risen on average to 36.7% of what they had lost. Even for the men who were in the highest caloric group, they were still 10% off their starting weight. But at the end of this phase, even those subjects who were on the highest calorie intakes, their overall physical condition was considerably inferior to their pre-starvation status.

What Keys discovered during this restricted rehabilitation phase is that calories, above all else, are the most important thing. Let me quote Keys directly here. He said: ‘Enough food must be supplied to allow tissues destroyed during starvation to be rebuilt. Our experiments have shown that in an adult man, no appreciable rehabilitation can take place on a diet of 2,000 calories a day. The proper level is more like 4,000 daily for some months. The character of rehabilitation diet is important also, but unless calories are abundant, then extra proteins, vitamins, and minerals are of little value’.

For most of the volunteers, this was the end of the experiment. They had the control phase, the restriction phase, and then the restricted rehabilitation phase. They’d spent a year of their life living under a football stadium, and now they were able to go off and return to normal life.

00:52:22

But for 12 volunteers, three from each of the four different restricted rehabilitation caloric groups, they stayed on for an unrestricted rehabilitation phase, which lasted for 8 weeks. This was where there was no restriction placed on how they could eat, but it was still carefully recorded and monitored. I say unrestricted, but this wasn’t actually true – and this was something I found out as part of the follow-up studies, but I’ll cover that in a bit.

During the first week of the unrestricted rehabilitation, the individual intakes varied from 4,400 calories to as much as 11,500 calories in a day. The average was 5,129 calories a day for the first week. Some of the men commented that they were still very hungry at the end of very large meals, even though they were unable to ingest any more food.

This increased eating concerned the research team, despite it being completely normal as part of recovery. They didn’t know this. One man, Henry Scholberg, remembered being taken to the hospital to have his stomach pumped. He’d eaten so much that he had developed gastric distention and had to be hospitalised. Many of the men reported vomiting unintentionally because they ate so much. Harold Blickenstaff, who was another participant, was sick on the bus on the way back from one of his several meals he had on Day 1. He found that he simply ‘couldn’t satisfy my craving for food by filling up my stomach’.

Seeing all of this, Keys’s team and the researchers decided to reinstate some kind of dietary control. During the weekdays, intake was restricted, and then on weekends it was totally unrestricted. I’m not sure what the actual amount of restriction was on the weekdays or how many weeks of unrestricted eating had occurred before this started. At the end of the restricted rehabilitation, the men in the highest caloric group were somewhere around 4,000 a day, so I wouldn’t imagine it would be restricted to any less than that. But I don’t have any details on it.

This change led to a pattern of ‘weekend gorging’, as it was described. The researchers estimated that the men initially ate between 50% and 200% more on weekends than on weekdays.

During the unrestricted rehabilitation period, the men rapidly saw health improvements, with some being almost instantaneous. In a three-day period, one subject gained six pounds and had his resting pulse increase from 36 to 60. Another had his basal metabolic rate nearly double in a three-day period.

It’s interesting to look at what happened to the subjects from a weight perspective. I found a fantastic paper that has only recently been released. It’s called ‘Physiology of weight regain: Lessons from the classic Minnesota Starvation Experiment on human body composition regulation’. It’s in the journal Obesity Reviews, so it does come with its biases and a focus on the obesity epidemic, but with that said, I think it was super interesting. I’ll link to it in the show notes.

What that paper has done is go back through all the data from the Minnesota Starvation Experiment to look at each individual’s weight changes as part of the experiment, including those in the unrestricted rehabilitation phase, and not just looking at weight, but looking at body composition.

As I mentioned at the start, there was a wide range of body weights, but there was also a wide range of body fat percentages at the start. What they wanted to see as part of this paper was how someone’s body composition impacted on weight loss as part of starvation, but also as part of the weight restoration phase.

Before I get to that, let me just start in generic terms, talking about the men as a group and their experiences, and then I can add in the extra detail from this paper.

00:56:45

All the men lost significant weight as part of the experiment. As a group, they averaged about a 24% loss of original weight, but this varied from person to person. During the restricted rehabilitation phase, once calories were high enough, weight started to be regained. As this weight was regained, the ratio of lean tissue restoration versus fat restoration was much more tilted towards fat gain. Fat went on much faster, and this was in higher amounts, particularly around the belly and the abdominal region.

For example, at the point at which their body fat percentages matched put to their pre-experiment levels, the men still weighed less than when they started. By the time that their lean body mass was restored to pre-experiment levels, abdominal fat was on average 40% higher than when they started.

But once this lean tissue reached the pre-experiment levels, the weight gain typically started to level out. With time, the fat levels then began to reduce. I say with time because for each of the men, this was different. When I recorded the original podcast on the topic, I mentioned that by 46 weeks of unrestricted eating, weight and fat percentages had returned to basically pre-experiment levels, but what I discovered as part of the follow-up studies (and I was able to correct in that second podcast) was that this is not the case.

Let me tell you what the participants remembered and talked about as part of the follow-up studies. I’m going to quote one of the studies here.

‘Based on the data gathered in the follow-up, changes in weight were more drastic and lasted longer than reported in the Keys study. The mean weight gain exceeding control weights recalled by 16 follow-up participants was 22 pounds’. (As an inside, in the Tucker book, the figure he uses is 27 pounds, but 22 and 27 are in the same general range.) Back to the quote: ‘Most took longer than 58 weeks to return to their control weight. Seven men had problems for 6 months to a year, five had problems for 2 years, one had problems for 3 years, and one had problems that resolved in 4 to 5 years. Three men described minimal problems with abnormal eating or being overweight. Their weight and eating patterns normalised within 6 months. Three men never returned to their control weight’.

I think this is hugely important because in the study and the way it was presented by Keys and subsequently by me in the original episode and by others was that this was all resolved within a year. So many people in recovery feel like they must be doing something wrong because they are 18 months in and they’re still not there, and yet the guys in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment were supposedly better in under a year. Or the men had stopped gaining weight and returned to their original size by 46 weeks, but they’re still gaining and it’s been more than a year, so what’s going wrong?

I just want to really set the record straight and say that the men didn’t only take a year to recover. Many of them took much longer, and they were only restricting for six months in comparison to many clients or people who have struggled for years or decades. The men didn’t have the exercise compulsion or the fear of eating or so many of the other facets that are common among eating disorders, which I’ll cover in a moment.

Most of the men did get back to a similar place, their original weight. In the Tucker book, just like with the quote that I read above, he mentions that three men never got back down to their control weight, but I’m not sure how much higher they were.

That is the information about the weight in more general terms. I want to go through now the specifics that were outlined as part of the recent paper, as it really fleshes things out in more detail.

01:00:48

When we lose weight, some of that weight will come from fat compartments and some of it will come from fat-free mass, which is everything else. Fat-free mass includes muscle, connective tissue, internal organs, bones, water. It is the body that is choosing what ratio is fat versus fat-free mass. This is fairly constant within an individual. As the paper states, within the population at large, the ratio is variable. Some people will lose more fat; other people will lose more fat-free mass. But for an individual, their ratio is fairly constant as part of losing.

The same is then true with weight going on. The ratio the body uses here is fairly constant, but the ratio for weight coming off isn’t the same as the ratio for weight going on. This is something I’ll come back to in a bit.

My comments here are also true irrespective of the composition of the diet. There was originally a belief that if the diet was higher in protein, this would mean that more lean tissue would be spared as part of the restriction phase, or that lean tissue would be built quicker if the rehabilitation diet was higher in protein. But this is not true, and this was demonstrate by the Keys study as well as other studies with anorexia recovery as well as childhood malnutrition.

The reason for this is that protein can be used for so many things in the body. It’s not just about rebuilding lean tissue; it really has endless functions, and protein can also be turned into energy as well. So what determines the ratio of the composition breakdown and the rebuilding is order regulated by the body. It’s not about the diet.

This is important to remember, because we live in a time where everyone is hyper-focused on healthy eating, and even in recovery people want to eat a healthy diet. That often means high protein with the belief that it will lead to less weight gain or building lean tissue quicker. But lean tissue isn’t the same as fat-free mass. It’s forgetting about bones and organs and connective tissue.

I’d say the same thing with exercise here. Doing high amounts of weight training in recovery and thinking that this is preferentially building up lean tissue – this is only one part of the equation. If there’s still not enough energy coming in to rebuild the other parts of the fat-free mass, your bones and your organs and your connective tissue, etc., that have been depleted, then creating more lean tissue won’t change this.

I mentioned earlier that despite the men’s total weight when starting the experiment, some had lower body fat percentages and others had higher body fat percentages. What this paper found is that those who had lower fat percentages to start with tended to lose higher amounts of fat-free mass as a ratio, and those who naturally had a higher fat percentage tended to lose fat at a higher ratio – which kind of feels like it makes intuitive sense that if you have a higher amount of fat, your body would lose a higher rate of fat.

But what’s interesting is that this happens from the start. It’s not that those who were leaner were originally losing lots of fat, but then their reserves ran out quickly so they had to switch to fat-free mass. Regardless of their size, their body was losing both fat and fat-free mass in a fairly constant ratio. For those who were naturally leaner, it’s more likely this ratio was skewed towards fat-free mass, and for those who were naturally heavier, their weight loss was skewed more towards fat.

For me, this is just another bit of evidence that demonstrates that bodies come in different shapes and sizes, and this is based on how the body auto-regulates. It has a size and shape preference, and regardless of what society wants to tell you that you should look like, the body has its own thoughts on this.

Something else the paper found was the more fat that someone lost, the more their basal metabolic rate was reduced. This was fat, not fat-free mass. Meaning those who had the lowest fat percentage to start with on average saw less of a reduction in basal metabolic rate, but those who had the highest fat percentage to start with who then lost more fat as part of the starvation saw a more marked drop in their basal metabolic rate – which feels counterintuitive in how we think about fat on the body. Fat is just this energy and if we lose it, it’s a really great thing, whereas we care about lean tissue and organs and bone and we feel we should be preserving it. But from a BMR perspective, it appears that the opposite is true, at least from this study.

This could explain why those who are in a larger body and have lost weight can be on such a low calorie diet and have their weight loss slow or stop altogether. Their BMR (basal metabolic rate) is reduced much more than people would expect. The narrative is often that they are hiding how much they’re eating or they aren’t very good at remembering what they ate, but the reality is that their body is now functioning very differently to someone who was at that weight and doing so naturally. This isn’t going to change anytime soon, and it’s not going to change without weight regain, because it’s really the fat levels that are controlling this basal metabolic rate.

In the article, they talk about the body having a memory of portioning, meaning that if you restrict, the body remembers what you used to be like and wants to get you back there. But this isn’t so straightforward. As I mentioned earlier, during the rehabilitation stage, the body prioritises fat regain over lean tissue and fat-free mass. This is actually more acute for those who started out the experiment with a lower fat percentage. The article refers to this phenomenon as ‘fat overshoot’. I’m going to quote it:

‘The degree of fat overshoot was found to be most strongly and inversely related to the initial body fat percentage, such that the leaner the individual, the greater the amount of fat overshoot’.

There is a reason for this. The ratio of fat-free mass to fat tissue that the body loses during restriction is not the same as the ratio when weight goes back on. The point at which the body stops gaining as part of the overshoot isn’t related to fat regain, but to do with the fat-free mass regain. Once lean tissue and bone and organs and all of that get back to pre-starvation levels, this is when it stops.

So if you started out with a lower fat percentage, the level of fat-free mass lost during this time is going to be higher. It’s then going to take longer to rebuild, or not necessarily longer, but a higher number of calories proportional to what was lost.

This also has an effect on hunger levels and the levels of hyperphagic response, as the article refers to it. Hyperphagic response is extreme hunger in more layman speak. Let me quote the article: ‘In the reanalysis of this data, the hyperphagic response assessed as the excess energy intake above control levels during the eight weeks of unrestricted refeeding was found to be driven by an integrated response from the deficit in fat-free mass, the deficit in fat mass, and the deficit in energy intake during the preceding control of restricted refeeding. These three factors together explain most (80%) of the variants in the hyperphagic response’.

It was all these three factors that mattered. So even if higher calories were provided and fat percentage was then above where the study started, if the fat-free mass or lean tissue was still less, the hyperphagic response or extreme eating continued. It was only after the lean tissue was recovered that this changed.

This is really important. I’ve seen so many treatment facilities who deal with anorexia talking about wanting to get someone back to a ‘normal’ weight, and this is when things will get better. But you don’t know just because of someone’s weight in and of itself where they are as part of recovery. Even knowing where someone started out tells you nothing, because just looking at someone, you have no idea what their fat-free mass levels are, and you have no idea of where the body wants to dictate as that being normal.

And this is on top of the fact that for the majority of people who have an eating disorder, they don’t look like they have an eating disorder in terms of our stereotypical view of it. Many people are never going to get to a normal weight range, even though they have an eating disorder. If someone is below the normal weight range, just getting them back to there tells you nothing about where they are as part of recovery.

You could be in a much heavier body than where you started and still be experiencing extreme hunger, and this isn’t because you’re broken, it’s not because you’re an emotional eater, it’s not because you’re a binge eater; it simply means that your body hasn’t repaired its fat-free mass stores to the level it deems appropriate. But with time and food, it will. You don’t need to intervene. It will do this all on its own when you can trust it and give it what it needs.

The same thing here is true if I look at someone who is a chronic dieter. This is something I talked about in my episode on weight set point theory. If you haven’t listened to that episode, I suggest checking it out; it’s Episode 114. What we often see with dieting is that over the years, it leads someone’s weight to be steadily increasing, as if their weight set point is increasing over time.

But I do wonder if this is truly someone’s set point increasing or simply that with each diet, weight is lost, but when weight returns, the ratio is weighted more towards fat rather than the fat-free mass, and then at some point their weight eclipses where they started before they went on a diet, but still their fat-free mass isn’t restored, and then it continues on, but the person has had enough, so they go on another diet. Weight is then lost again until they can’t keep it up anymore, so the diet is broken and the regain starts to happen. Again, the body has a preference for fat regain over fat-free mass, and what happens here is just constantly repeating this situation where it takes a higher and higher weight before fat-free mass is restored. But each time, the person doesn’t get there and instead goes on another diet.

In the eating disorder recovery space, there is a lot of talk about fat overshoot, which is what is seen in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment. The men ended up at weights that were higher than where they started, and they were higher because the body fat percentage was higher than before the experiment. But once the body had restored the fat-free mass, this is when the body started to naturally change and come back down to levels that were similar to where they started.

This is where the idea of the memory of petitioning comes in. The body remembers how it used to be and takes you back there. But it can take time for this to occur, and we saw this with the men. This took anywhere from six months to five years. For three men, they mentioned that they never returned to their control weight, but I don’t have any details on what that difference was. And again, keep in mind that these men were only doing this once and this was only over a six-month period.

01:13:23

As an aside, I think the talk of fat overshoot and how much I see it going on – while I think understanding this is helpful, I do think too much is made of it. It can be unhelpful to put a lot of focus there, where people are starting to question, ‘Am I in the overshoot? Is this going to spontaneously come off? How long is it going to be before this is going to happen?’

Eating disorder recovery is about getting your life back. It’s about nutritional rehabilitation and having the various organs and systems of your body working well again and having repair taking place. It’s about neural rewiring in the brain linked to how you think about food and exercise. It’s about brain repair more generally. It’s about learning coping skills. Recovery is about getting past a focus on weight and how much weight impacts on choices around food and exercise.

If the focus is constantly on the fat overshoot, this keeps you in the eating disorder mindset, and I think it actually prevents the change from occurring. There’s the paradoxical fact that when you’re able to accept something, it’s at this point that you’re able to change it – but without acceptance, change can’t happen. I do think the same is true here. When you can forget about the fat overshoot and live your life, this is when it’s more likely to occur as long as the fat-free mass is restored.

I want to read one final quote from the study because I think it sums things up nicely: ‘Over the course of their evolutionary history, humans, like many other mammalian species, have been faced with periodic food shortages and frequent exposure to famines. Consequently, it is plausible that what constitutes the normal physiology of weight regulation must have evolved within the constraints of large fluctuations of body weight and body composition. In this context, the control systems underlying body composition auto-regulation must have evolved to optimise not only the survival capacity of the individual during prolonged periods of negative energy balance, but also the recovery of the individual’s survival capacity when food availability improves’.

I do truly believe that our bodies are infinitely intelligent. Just because your recovery process looks different to someone else’s, doesn’t mean that you are broken or that your body is doing it wrong. It is doing the exact right thing that needs to happen for you. Any problems you have with this are about your own expectations or your eating disorder thoughts. If you can give your body what it needs from a food and rest perspective, it can take care of the rest.

This isn’t to say that this is all that someone needs for recovery, because eating disorders can be about many things that are separate to just malnutrition. But at least from the physical perspective, your body knows how to heal and does so in the right order, even if that order is different to the way you would like it to happen.

01:16:35

I want to go through some other comments or insights gained from the follow-up papers. This continues to connect to the weight regain and the men’s experiences and the men’s memories.

Many of the men remembered feeling a loss of control over eating during the early refeeding period. Four men stated that they felt like eating more or less continuously for a long time. Jasper Garner, one of the participants, described it as ‘a year-long cavity that needed to be filled’. Six of the 19 men, so 32%, reported binge eating, which is defined as eating large amounts of food in a short period of time along with a feeling of loss of control of eating, and that this was particularly happening during the initial feeding period when the dietary restrictions were finally lifted.

Personally, I see a problem referring to this kind of eating as a binge. The word ‘binge’ has such a negative connotation, and this eating is really a response to starvation. It’s the body being helpful and sending signals to you to get you to eat so it can start to repair the damage of not receiving enough food.

After a few weeks of calorie intakes that would go up to 10,000 a day, this seemed to level off at around 3,200 to 4,500 calories per day, although some continued to eat more than this.

During the rehabilitation, seven men were concerned about accumulation of fat in the abdomen and buttocks, and five of these men reported that during or after the rehabilitation phase, they were bothered by how fat they felt. Three months after the start of the rehabilitation, one man wrote in his personal notes: ‘During this week, I regained my top control weight. However, it is certainly not in the same places as the pounds I had on me when I came to Minneapolis. My arms, thighs, buttocks, and midsection are all fuller than I can ever recall. My face is also fatter. However, these reactions may be conditioned by what I got used to during the semi-starvation’.

That’s seven out of 19 who were interviewed, or 36%, that were concerned about their weight as part of recovery, but I don’t know how concerned they were or how much this impacted on their life.

For some, the rehabilitation period proved to be the most difficult part of the experiment. Roscoe Hinkle, who was one of the participants, noted that rehabilitation ‘turned out to be worse for me than anything else. I had troubles because I didn’t really feel that I was coming back at all’.

During rehabilitation, the scores indicating recovery from depression correlated with calories received. Basically, as calories went up, depression improved, although it wasn’t completely linear. This is basically the same with all the scores with the MMPI. More food consistently led to better psychology.

Keys also stressed the dramatic effect that starvation had on mental attitude and personality. He argues that democracy and nation-building would not be possible in a population that did not have access to sufficient food, which is also connected to that quote that I read before by the psychologist.

The men reported that reduced dizziness, apathy, and lethargy were the first signs of recovery and that feelings of tiredness, loss of sex drive, and weakness were slow to improve. Robert McCullagh, who was one of the participants, noted that he could tell he was beginning to recover when his sense of humour finally returned.

Many of the men admitted that for many years, they were haunted by a fear that food might be taken away from them again. Ten of the men indicated that their perceptions and perspectives regarding food were permanently altered by the study. I don’t have any more details on this, but this kind of feels fairly standard as a response. I don’t think it really indicates anything particularly negative. If I’d been starved for a period of six months and had my food amounts dictated by a lab, I’d imagine it’s something that would change how I saw food forever.

In 1991, during a meet-up that many of the men attended, a questionnaire was handed out, and 80% of the men who were in attendance agreed that ‘the experiment increased my capacity to cope with anxiety’. More than 60% of the men said they would encourage their own sons to participate in a similar experiment – which is pretty huge that 45 years on, they remembered the experiment in such a positive way. But I would say that I think time has probably mellowed how the men think of this experiment. I bet if the men were asked six months or a year after the experiment, they wouldn’t be making comments like they’d encourage their sons to participate. I really think this shows the power of how good the mind is in its ability to recover from difficult situations and the power of stories that we tell ourselves.

For all the men as part of the study, they had no lifelong physical, cognitive, or emotional adverse effects, despite the suffering that happened during the experiment. All the participants ultimately led interesting and productive lives and went on to be college graduates. Six attainted PhDs, one a master’s; six were college professors, four were teachers, two were ministers, an architect, a lawyer, an engineer, and a social worker. One even received the highest civilian honour, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, for his decades of work in politics. All the men interviewed as part of the follow-up studies felt that they had led useful and interesting lives.

01:22:35

The final part of this episode is I want to compare what the men experienced as part of the experiment to what someone with an eating disorder experiences. Like I said at the beginning, this is an experiment that is so often referenced with eating disorders, so where are the similarities and where do these end?

In terms of similarities, I’ve already covered most of this. When I went through the long list of physical, mental, and emotional symptoms that the men experienced, these are similar to an eating disorder – the reason for that being that they are triggered by starvation and malnutrition, which is the same with an eating disorder.

This is true irrespective of the type of eating disorder. I think it may be easy to think there are similarities here with these men and someone with anorexia, but it’s not going to be the case with binge eating disorder – but really, with all eating disorders, restriction is at the heart of it. Outside of a binge, someone is restricting. They may be exercising in a way that is more than the body can handle. So it doesn’t matter if there are moments where restriction is punctuated with more food coming in; the body is still in a malnourished state.

Again, this is true irrespective of what the body looks like. Malnutrition doesn’t occur only when the body becomes emaciated and matches up to our stereotypical view of what starvation looks like. It can be occurring in people of all body shapes and sizes. So just because your body doesn’t look like the men did at the end of the experiment, doesn’t mean that restriction hasn’t been occurring or hasn’t been impacting the body.

There are similarities between this experiment and an eating disorder in terms of symptoms, and there’s also the similarities as part of the recovery process, with the weight regain and how the body prioritises this, which I went through.

01:24:30

What about the differences? The first difference was that the starvation was being forced upon the men by what the experimenters dictated, but with an eating disorder, it’s self-imposed. This is a really big difference.

For example, the participants dreaded calories going lower. They feared it. The only reason they were maintaining this reduction was because of the experiment. If they’d been offered more food, they would’ve eaten it. This was exactly what happened in the midpoint when they had the relief meal, or when the calories were increased as part of the restricted rehabilitation. They ate everything they were given, and then during the unrestricted rehabilitation, they ate as much as they could get in.

This is the opposite of an eating disorder. Typically the goal is restriction and then further restriction. If someone’s intake drops down, this new lower figure becomes the norm, and everything above this feels scary. Increasing eating is a source of tremendous struggle, and this is not what the men experienced.

Even for those with an eating disorder that is punctuated with times of eating more, there is guilt and shame for having those eating sessions, and the goal is still restriction.

The same is true with fears about food. It’s common with eating disorders to have ‘good’ and ‘bad’ foods, foods that are fear foods and things that feel impossible to eat. Food becomes seen as a threat, and certain foods spike these threat levels more than others. But none of this happened with the men. They simply followed orders, and if they were allowed to eat more food, whatever the food, they did so.

None of the men interviewed reported periods of increased activity. They all recalled a gradual decrease in strength, in co-ordination, in endurance, and a sense of lethargy paralleled by a curtailment of any form of spontaneous activities. Again, this is typically different to those with eating disorders, where exercise becomes a compulsion and it can be like the malnourished state turns on a need for movement and exercise. This is the opposite of what the men experienced.

In Tabitha Farrar’s book, Rehabilitate, Rewire, Recover!, she talks about the migration theory with anorexia and that this can potentially explain the need to move and never wanting to sit down and be still. This was just not the case with the men. All of them reported being tired and lethargic and wanting to do as little physical activity as they were allowed.

The reasons behind the men’s behaviour are also different to an eating disorder. For the men, it was part of an experiment. For those with an eating disorder, it can be about many different things. It can be a coping mechanism and a way of dealing with anxiety and trauma. It can be a way of gaining control or a semblance of control. It can be because of body image concerns and trying to change how someone looks for seeking love or approval.