Over the last handful of decades, society’s belief in the healing power of food has grown exponentially. One’s diet is seen as the solution to more and more health problems.

Running parallel to this belief in foods healing ability, there has also been an increased fear of eating the wrong foods. That while food has the power to heal, it also has the power to harm.

This change has been happening at the level of society as well as at the individual level. And maybe you have noticed this yourself.

At first, learning about the importance of food felt exciting. You opened the door to this world of knowledge you didn’t have before. You felt empowered and had a sense of agency. This really is within my hands.

Typically, at first, when you made changes, everything felt like it was improving.

You lost weight, had more energy, and/or improved your digestion.

You got positive feedback from friends.

You found books or an online community that was in alignment with this new way of being.

Maybe you even decided to study nutrition, dietetics, or health coaching.

All of these changes reinforced that you were on the right path and further fuelled these new beliefs and habits.

But with time, this changed. What first felt straightforward, now feels confusing.

Health problems have come back and/or new ones have arisen.

Things that used to work before have stopped working.

You’ve become stricter with what you will and won’t eat.

At this point you find yourself stuck and confused (although this may feel hard to admit). What used to feel like freedom has morphed into rigidity and inflexibility.

Orthorexia is something I’ve been talking about and helping clients with for the last decade. And while it is something that is becoming more widely known, it has a stereotype of what it looks like. This means many people would never think of it as something affecting them.

As part of this article, I want to explain what orthorexia is, some of the misconceptions about it and how to find your way out.

Orthorexia Nervosa is a type of eating disorder, just like anorexia nervosa or binge eating disorder. Its name means “fixation on righteous eating.” It’s a condition associated with eating “perfectly”, “clean” or “pure” and with heightened fears about “unhealthy food.”

Eating disorders are diagnosed using the DSM-5, which is the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. There isn’t a specific diagnosis for orthorexia, but it is a subtype of the eating disorder Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID).

There are three subtypes of ARFID and one of these is about a fear of adverse consequences of eating. Broadly, this can encompass fears of swallowing, choking, nausea, vomiting, and pain. Or, in the case of orthorexia, the fear of adverse health outcomes from eating certain foods.

Orthorexia is a term that was first coined back in 1997 by American physician Steven Bratman. Although it wasn’t until more recent years that it entered into public awareness, mostly in the last decade.

Interestingly, the awareness of orthorexia started around the time that “clean eating” became a popular diet or way of talking about food. Its focus is primarily on unprocessed and unrefined foods, and while clean eating is still a thing these days, its popularity was at its height between 2012 and 2017.

Earlier I said that orthorexia is associated with eating “perfectly”, “clean” or “pure,” which means that it can feel like orthorexia and clean eating are the same thing. Or that orthorexia is when someone takes clean eating too far.

But the reality is, orthorexia is much broader than this. Pure, perfect and clean are all subjective terms. Yes, it can mean green smoothies, acai bowls and only eating organic food. But it can also mean:

Orthorexia can also be connected to not just the type of food, but how one eats. So, following intermittent fasting and having an 8-hour eating window each day. Or believing that humans should eat just one meal a day and rigidly sticking to this eating pattern.

Now, just because you are eating in the above ways or have these beliefs about food does not mean you have orthorexia, I’ll get on to part in a moment.

But I want to get across that we have a stereotypical view of what orthorexia means and in reality, it can happen with strict adherence to any diet and the fear of deviating from this way of eating.

As I mentioned at the beginning, as a society our belief in the healing power of food has grown exponentially. This has led to an increased focus on the strain on our health systems from “lifestyle diseases” and the belief that preventing or reversing chronic disease is a matter of personal responsibility. And the key driver for this is changing one’s diet.

Because of the way we now value food and diet, it can often be hard to comprehend the concept of orthorexia. To some, it can feel like people are being demonised for wanting to take care of their health.

“There’s nothing wrong with being healthy. And if someone wants to take this even further, and really prioritise their health, what’s wrong with that? If anything, we need more of this in society, not less!”

Unfortunately, what’s often missed is that orthorexia isn’t enhancing someone’s health. While this may be the intention, the actual outcome is very different.

The best analogy I’ve come up with for understanding this is someone who has OCD and can’t stop washing their hands. We don’t look at this person and believe there is nothing to worry about because being clean and hygienic is a good thing. We realise that all this extra washing of hands isn’t making them extra clean, it’s negatively impacting their life.

Well, the same thing is true with orthorexia. The focus on health isn’t supporting health, it is negatively impacting the quality of life. And this is true even if someone appears to be “fit” and “healthy” and is living up to the stereotype of what society tells us we should be doing.

Orthorexia, like all eating disorders, is hard to neatly capture. Over the years there have been different tests and assessment tools to help with diagnosis. Personally, I believe these can be useful but they should be seen as just one piece of information, rather than the deciding factor.

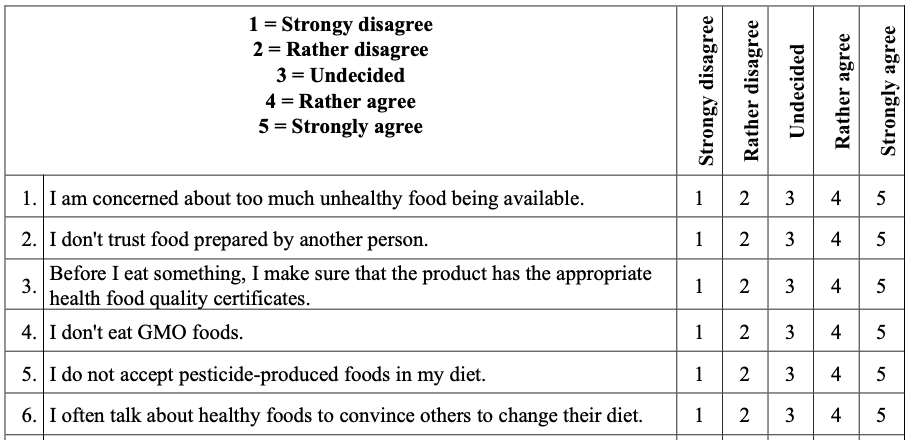

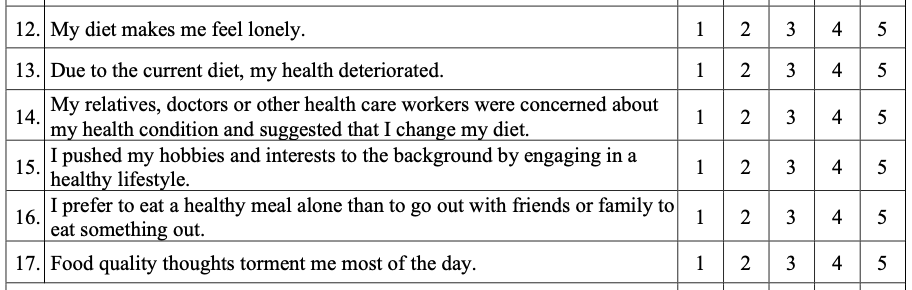

One of the most recent assessment tools for orthorexia assessment is called the Test of Orthorexia Nervosa (TON-17), which you can see in full here.

While this has its merits, I honestly believe that this tool is too narrow in its questioning and is viewing orthorexia through the “clean eating” paradigm. But despite this, it still has its use. And this can most easily be seen when we look at the intent behind the questions and how they’re structured.

The 17 questions on the form fall into three categories. These are:

Category 1 Control of food quality – this is asking about how much someone is monitoring the quality of food that they eat. In effect, this is about dietary restraint and the importance of selectively restricting foods. Here are the questions from this section:

Note: It’s this first category of the form that I think could be amended and may need to be individualised, depending on someone’s specific diet of choice.

Category 2 Fixation on health and a healthy diet – this is asking about how someone is prioritising and monitoring their health and the connection they make between diet and health. Here are the questions from this section:

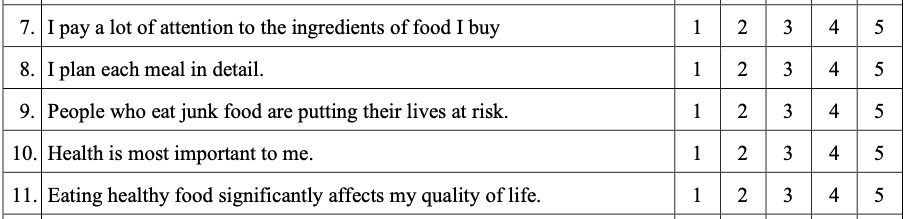

Category 3 Disordered symptoms – this is asking about the negative ways someone is affected by these beliefs about food and the practices followed. It includes physical symptoms, psychological symptoms and the impact on relationships. Here are the questions from this section:

While this third section is asking the respondent about their subjective experience, it is also useful for someone who is trained in eating disorders to have their own perspective on this section. This is because:

As someone’s health deteriorates with orthorexia, so too can their awareness to notice these changes. Or to connect them to their preferred way of eating.

Often, friends, family and doctors are praising someone on their health and fitness as things are getting worse. And if symptoms do arise, they are told it isn’t connected to how they are eating or exercising.

Often, someone’s hobbies can become their healthy lifestyle and it doesn’t feel to them like their interests and hobbies have been pushed to the background. It can feel to them like how they enjoy spending their time has simply changed.

For me, these three categories capture how orthorexia plays out. That specific practices and behaviours, connected to specific beliefs and fears create a detrimental outcome in one’s health and life.

And while recovery from an eating disorder encompasses many things, we can use these three categories as a guide for how to find your way back to true health.

Let’s start with the third category above – the disordered symptoms.

Most of the symptoms that are arising with orthorexia are connected to malnutrition and the body being in an energy-depleted state. I say “most” because there are often symptoms that predate orthorexia, which can often be the reason you first started going down the route of trying to “fix your health”.

But while health issues can have been occurring previously, these can increase because of the changes to how you eat and the restriction and energy-depletion that ensues.

This could be due to the total amount of energy coming in being less than what your body needs. Equally, it could be due to a specific macronutrient that is missing or in low amounts. So low amounts of carbohydrates, protein or fat.

When you have fewer resources coming in than are needed, the body has to triage its allocation of these resources.

Certain functions are turned down and there’s less energy to run them, with digestion being a prime example (something I cover in detail here). With less energy coming in there can be less hydrochloric acid in the stomach or fewer pancreatic enzymes. This means that food isn’t digested and absorbed as well as it could be and symptoms, like gas, bloating, or pain for example are more likely to occur.

Other functions can be completely shut off, with reproduction being a perfect example (something I discuss here). Reproduction is not important for short-term survival and if the body has limited resources, it will shuttle these resources to essential functions.

Sadly, this can become a vicious cycle. As new symptoms arise or current symptoms get worse, further foods are cut out, as you try to figure out what is causing the problem.

This new restriction might create a honeymoon period where temporarily things do feel a little better. But with time things actually get even worse.

And so, something further is cut or reduced and the cycle repeats itself. (If you want to hear real examples of how this plays out, you can listen to podcast interviews here and here).

Recovery is about reversing this. Bringing in more energy so that the body can rehabilitate and repair. And if it is specific macronutrients that have been absent, then these must be part of the increased energy that is coming in.

The other two categories from the Test of Orthorexia Nervosa (TON-17) relate to beliefs and fears connected to food and health and the subsequent action taken because of them.

From my perspective, there are two important ideas to understand with this. And when combined, this is how beliefs and fears are changed.

The first is that, to borrow a phrase from Deb Dana, that story follows state. The state that the body is in impacts the thoughts, beliefs, memories and feelings that naturally arise.

While we like to think that we are the author of our thoughts, the reality is that thoughts think themselves. We merely become aware of them as they enter our consciousness. As an example, notice the difference in the quality and content of your thoughts:

If you’ve had 3 hours of sleep versus you slept peacefully all night

If you’re ravenously hungry versus you are satisfied and content

If you feel angry versus you feel calm

The amount of energy coming in, the amount of sleep you’re getting and the emotions that you’re feeling, are all connected to and/or impact the state that you’re in. And this state then impacts the kinds of thoughts and beliefs that naturally arise. (Something I go into much more detail on here).

This means that changing your state is incredibly important to changing your thoughts and beliefs. And while there are many ways to change your state, the most important at the beginning of recovery, is more energy. Truly, nothing else comes close.

(Note: the Minnesota Starvation Experiment is a fantastic example of this, showing how energy depletion not only affected physical health, but also psychological health. This is a detailed podcast (with a transcript) all about it).

The second idea to understand is that orthorexia is an anxiety disorder. The way certain foods are or aren’t eaten is collectively known as avoidant coping behaviours.

The more these are practised, the more normalised it becomes. So, with time, it makes doing something different more challenging.

With anxiety disorders, the thing that perpetuates them is avoidance, as avoidance begets more avoidance.

For example, let’s say you have some concerns about bread but you still eat it. If you stopped eating bread for one day, having it the next day is not too difficult. If you’ve stopped eating it for a month, now it’s become more challenging. If you’ve stopped eating it for a year, it’s even more challenging to reintroduce it.

With anxiety disorders, the thing that overcomes them is exposure. Where exposure means doing the opposite of avoidance and doing the thing that you are afraid of.

Now, this can be done gradually, starting with things that feel less scary and building up over time. But the thing to know is that confidence comes after the fact, not before it. It’s by taking action and eating the bread for example that the fear dissipates.

Trying to get the fear to disappear before taking action doesn’t happen and it just leads to staying stuck. Because you don’t think your way into acting differently, you act your way into thinking differently.

(Note: This is a topic I go into in much more detail in this article and this podcast episode with Sasha Gorrell)

When we combine the two ideas above, it means that recovery from orthorexia is about taking action.

Taking action so that the body has more energy coming in and your state can change.

Taking action so that the fears that naturally arise when eating certain foods no longer arise.

With orthorexia, there is a huge gap between the intention and the outcome.

The intention is for it to improve your health. And with this improved health, for you to be able to live a vibrant life of freedom.

But the actual outcome is that it’s made your health worse. But more than just physical health, psychologically things have become rigid and characterised by black-and-white thinking. So not only does it not enhance the quality of your life, it negatively impacts it (and significantly so).

Is this the place you find yourself in? Would you like things to be different?

I’m a leading expert and advocate for full recovery. I’ve been working with clients for over 15 years and understand what needs to happen to recover.

I truly believe that you can reach a place where the eating disorder is a thing of the past and I want to help you get there. If you want to fully recover and drastically increase the quality of your life, I’d love to help.

Want to get a FREE online course created specifically for those wanting full recovery? Discover the first 5 steps to take in your eating disorder recovery. This course shows you how to take action and the exact step-by-step process. To get instant access, click the button below.

Share

Facebook

Twitter