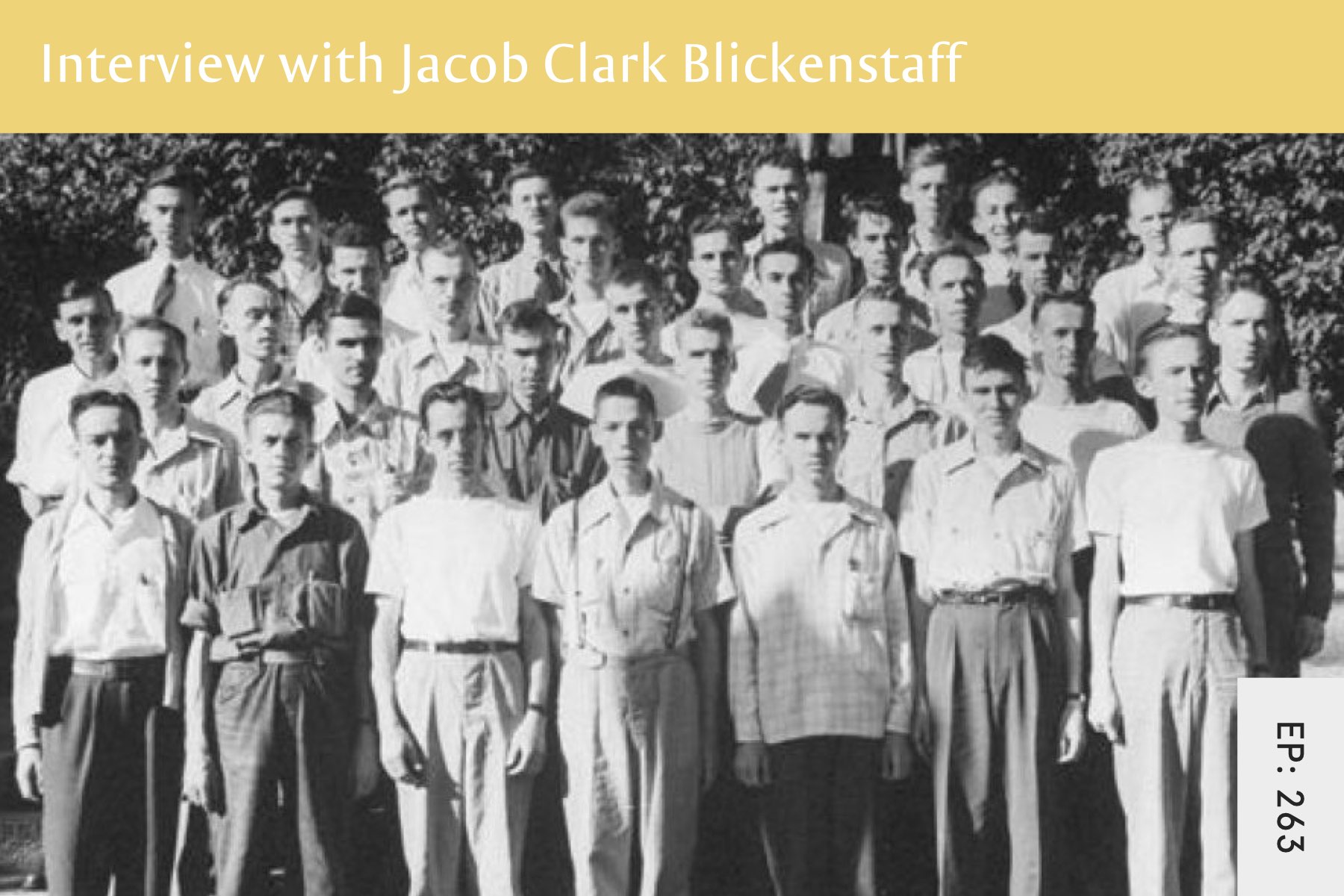

Episode 263: Today on the show I'm speaking with Jacob Clark Blickenstaff, his father Harold Blickenstaff was one of the participants in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment.

As someone who is endlessly fascinated with the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, it was an honour to be able to chat with Jacob about his father’s experiences and how this played out in Jacob’s life too

00:00:00

00:06:13

00:13:00

00:20:00

00:25:51

00:27:38

00:34:16

00:35:37

00:40:20

00:44:01

00:48:41

00:52:29

00:00:00

Chris Sandel: Welcome to Episode 263 of Real Health Radio. You can find the show notes and the links talked about as part of this episode at www.seven-health.com/263.

Hey, everyone. Welcome back to another episode of Real Health Radio. I’m your host, Chris Sandel. I’m a nutritionist who specialises in recovery from eating disorders and disordered eating and really just helping anyone who has a messy relationship with food and body and exercise.

Today on the show it is a guest interview, and today my guest is Jacob Clark Blickenstaff. Jacob is actually the son of Harold Blickenstaff, who was one of the participants in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment. If you’ve been following my work for any length of time, you’ll have probably heard me or seen me reference the Minnesota Starvation Experiment. I’ve also done three past podcasts on it, with the most recent one being Episode 226. This was a real deep dive into the experiment, pulling together everything that I’d learnt about it and how and why it’s such an important study for understanding eating disorder recovery.

If you’ve not listened to that podcast before, then I highly suggest that you do. And if you’ve never heard about the Minnesota Starvation Experiment before this, then I probably suggest listening to it before this one, as it will make a lot more sense if you do it that way round.

This year, Malcolm Gladwell’s podcast called Revisionist History did a three-part episode of the Minnesota Starvation Experiment. He’s a fairly big name in the publishing world. He’s one of my favourite authors; I think I’ve read all of his books. He has a very successful podcast as well, and a whole podcasting platform now. So it’s great that he did these podcasts on the experiment and that it’s getting more exposure. I’ll also link to those episodes in the show notes, and I suggest checking them out.

A lot of the information for the Revisionist History episode was based on a follow-up study. The original experiment was done in 1944 and 1945, and then in 2003 and 2004, they interviewed 18 of the original participants from the original study. This was then released as a paper in 2005, and the paper was called ‘They Starved So That Others Could Be Better Fed: Remembering Ancel Keys and the Minnesota Experiment’.

What I was not aware of, but found out because of the Revisionist History episode, was that each of these 18 interviews with these participants were actually recorded and saved as oral histories and are stored in the archives in the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Anyone can listen to them; you just have to go there to do so. Seeing as I live in the UK, far away from Washington, D.C., I have reached out to Revisionist History to see if they have the transcripts for each of these interviews, and if they do, if they could share them with me. I’m waiting to hear back. If I do hear back and they are able to provide that information, then maybe another episode on this topic coming.

But it was because of this renewed interest in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment that Jacob got in contact with me and we recorded this conversation.

For me, this isn’t so much a deep dive into the Minnesota Starvation Experiment and the outcome of it – although we do touch on this – but is more a look at the history of the time, looking at the little-known history of conscientious objectors, and really the life of Harold Blickenstaff before, during, and after the experiment. As someone who is endlessly fascinated with this experiment, it was a real honour to be able to chat with Jacob about his father’s experience and also how this played out in Jacob’s life, too.

So, let’s get on with the show. Here is my conversation with Jacob Clark Blickenstaff.

Hey, Jacob. Welcome to Real Health Radio. Thanks for joining me today.

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: Happy to be here to talk with you.

Chris Sandel: The reason we’re chatting today is that your father was part of the Minnesota Starvation Experiment. It was about a month ago or so, a bit over a month ago, that you left a message on one of the episodes that I’d done on the Minnesota Starvation Experiment of “My father was Harold Blickenstaff, who is quoted above. His relationship to food was forever changed by his participation in the experiment. He never left food on his plate in my experience, and there basically wasn’t anything he would refuse to eat. If you’d like to talk about any of this, let me know.”

As soon as I saw that message, I reached out to you and we had a conversation, and then I asked would you be up for having a more in-depth conversation that we record as part of this podcast and you said yes. So that’s how we’re chatting today. I guess it will all be about the starvation experiment and what you know from your dad’s experience.

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: Great. I’m happy to be here and have the conversation. It was very interesting to me to find your podcast and your work on this through doing some Google searching. A friend told me, “I heard about a podcast about the starvation experiment”, so I started doing some searching and yours was one of the ones that came up.

Chris Sandel: Yeah. We talked about this earlier; Revisionist History, Malcolm Gladwell’s podcast, for the final three episodes of this season he has done episodes all about the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, so I think it’s probably entering into a lot of people’s minds and consciousness in a way that it hasn’t for a while. I imagine this is something that is going to come up more in searches.

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: Yeah.

00:06:13

Chris Sandel: What had your father done before the war? Obviously, this experiment took place towards the end of World War II. What was your dad doing before that? Was he working, was he at university?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: He was a student at a school called Manchester College in North Manchester, Indiana. It’s a college that is run by the Church of the Brethren, which was the church that he grew up in. He and his older brothers were students there as the war got started.

Chris Sandel: And he was a conscientious objector, as were all of the people who were in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment. Do you remember him talking about this at all and what it was like for him to take this stance and how it was received by those around him?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: Yeah, it was part of the family story to know about conscientious objection for a variety of reasons. One is that his father, my grandfather, was a conscientious objector during the First World War. The provisions were much more limited in the United States then, so my grandfather went to prison. He was drafted, refused a direct order, was court martialled and was imprisoned for a couple of years as a conscientious objector. He was in the Church of the Brethren, which is one of the historic peace churches in the United States.

By the time of the Second World War in the United States, there was a better system for conscientious objection, so my father applied for CO status and was granted CO status. Some folks had more challenge with that because individual draft boards had the ability to decide how they were going to designate someone. My father’s family history meant that he could easily establish that he had a religious basis for his objection, which was required. A practice and belief in his family and in himself that meant it was okay, that the board did grant him CO status.

He told that story. He told about the different kinds of service he did, which I can talk about in a little bit. He did also say that after the war he became a classroom teacher of history at the high school level, and he did not share about his CO status with his students for decades after the war, in part because he knew what had happened to his father. His father, even though his record was expunged by a presidential pardon in the 1920s, when folks found out that he had been a CO, he usually lost his teaching jobs. My grandfather only had teaching jobs for a year or two at a time and had to move around from one small town in Indiana to another. So my father did not share his CO status much outside of the family until probably the 1960s or ’70s.

Chris Sandel: Wow. That’s an interesting part of history. Did he have friends that were outside the Brethren and know families outside the Brethren, and what was their take on his CO status during the war?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: My understanding is that he was well-supported because of the community. He came from Church of the Brethren; in his role as a CO, he met folks from other religious backgrounds – Quakers, Mennonites, and there were some other folks, I think some Seventh-Day Adventists who were COs. He wrote in an autobiography of his that his experiences during the war meant that he met a much wider variety of folks than he had grown up among, because he’d been in northern Indiana, southern Michigan – a fairly narrow zone of the United States, and mostly in that Brethren community. So his experience broadened to understand other religious backgrounds more.

After the war and when he moved to California, California does not have a significant Brethren population, but there are some Quakers, so he and his family were more part of the Quaker tradition after the war.

Chris Sandel: What activities had he done during the war before getting involved with the Minnesota Starvation Experiment?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: A few. The Civilian Public Service had work camps around the country, so folks who were in the public service as COs would move from one work camp to another over time. He worked on trail building for the Blue Ridge Parkway, which is a long-distance hiking trail in the mountains of the middle-eastern part of the United States through the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Another site that he worked, which was fairly common for COs, was he was an attendant in a mental hospital. The particular mental hospital he was working in was one that served veterans, so it was a Veterans Administration mental hospital in the eastern part of the United States, I think, New Jersey. There he was an attendant in the ward; he had overnight supervision duties, he worked sometimes supporting doctors when a patient was receiving shock treatment. A lot of fairly intensive experiences doing that.

Those were the majority of this things before the starvation experiment. After the starvation experiment was over, another service that he did was in Florida, there were programs to build sanitary latrines in communities that didn’t have proper sewage disposal, and it was a way of controlling for hookworm, which was a big problem in that part of the country in very poor communities. So there was a CO work camp to build and install those latrines in a very poor rural part of Florida.

Chris Sandel: I know that there were other experiments that happened with COs where they were getting picked as part of that. Was he involved in any other experiments?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: No, the only experiment that he was part of was the starvation experiment.

00:13:00

Chris Sandel: Do you know how excited or not he was when he was picked as part of the experiment?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: I think it was interesting to hear from him and read when I read his notes that his motivations were around – folks doing the starvation experiment were housed at the University of Minnesota, so they would have access to coursework. He was excited about that. He was excited about living underneath the football stadium and getting to go to football games for free. He’d been a high school football player and athlete.

So I think the setting was exciting to him. I think he and maybe one other person he knew applied together; I don’t know if they both were accepted. It seems like he sometimes chose assignments by he and a buddy who he’d met at a previous work camp would say, “We’ve heard about this opportunity. Let’s apply for this one together.” So then they would go to do the next thing.

He was – he described it as being one of the last ones selected. They chose I think 36 out of over 300 applicants, and he was one of the youngest, if not the youngest subject in the experiment. So I think he was excited by the things around it and then also to be able to do something that put his body on the line and showed he would be able to say to someone else, “I was a CO not because I was afraid of physical discomfort or physical harm, but because of what I believed in.”

Chris Sandel: How old was he? You said he was the youngest or one of the youngest.

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: He was just around 20 years old.

Chris Sandel: I don’t think anyone really knew what they were getting into when they joined, but did he have any anticipation? Do you know if he had any thoughts of what would occur?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: I think he knew it was going to be potentially physically challenging, but I don’t think anybody going into it knew what to expect.

Chris Sandel: Did he talk much about it? A lot of the referencing you’re making here is like “I read this in his autobiography or I’ve found out about this afterwards, more from listening to a recording or writing.” How much did he personally speak about it with you?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: It wasn’t something where he would say, “Sit down, I’m going to tell you this story.” He was not that kind of a talkative person. He was a fairly reticent person, a quiet person a lot of the time. But I triggered him telling me about it sometimes with language that I would use. As a kid, if I said, “I’m starving”, he would say, “No, you’re not. This is what it means to be starving because I had this experience.” Or if I said, “I’m really, really hungry”, he’d say, “Okay, there’s an apple over there.” I’d say, “No, I don’t want an apple” and then he would say, “No, you’re not really, really hungry, because if you were really, really hungry, you would take the food that was offered to you.”

So I heard some about it growing up from that, and then when I was in high school, I had a nutrition course that was part of health education and as part of that course we were to track our food for a couple of weeks and write up a report. He saw me doing that and he said, “Are you weighing anything that you’re eating?” I said, “No.” He said, “It’s not going to be very accurate, then, because when I did this thing, everything we ate was weighed and they knew exactly how many calories we were eating.” That got me interested enough that I interviewed him and wrote a report for that nutrition course about the starvation experiment. A high school three- or five-page report that was a way for him to tell me the story.

In our home, we had a small book that was written about the experiment that was guidelines for folks with the results of the study. It was guidelines for folks who were going to be doing nutrition rehabilitation work, and inside that were a couple of snapshots of him from the experiment. So it was in the fabric of the family, but not a regular “Sit down and Father will tell you the story of the starvation experiment again.” More he would illustrate his points with things from that experience. I was a kid who loved to read, so I found the books and was like, “Oh, that’s you? Wow, that’s crazy. That doesn’t look like you.

Chris Sandel: Do you remember what you first thought when you heard about the experiment and trying to think about how it was for your dad, or just like, “Wow, they did this kind of experiment”? What were your thoughts when you heard about it?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: As a young kid, there was some annoyance that he was this way about food, that I couldn’t say certain words that I heard my friends say. That was kind of irritating as a little kid. As I came to better understand – and then I needed to register for the draft when I turned 18, because we’ve had draft registration in the United States for a very long time – then I had a lot more conversations with him about what being a CO was and things like that. So then I definitely had a sense of pride that he had been involved in something so unusual.

Then I’ve encountered it again; I have a degree, a PhD, in science education. So I had to do some courses around research ethics, so I understand, yeah, this is an experiment that would never happen anymore. That’s a lot of what Malcolm Gladwell is talking about: why this experiment would never be done again.

So I would say my thinking about it has grown and changed over time, but it’s been a background piece to understand. I’m the child of one of 35 people who had an experience that no-one else had, and they were documented in a way that no-one ever was, so that’s been interesting. It’s a point of pride to say my dad, while it was sometimes challenging to be his son, also there are things about him that I’m very proud of.

00:20:00

Chris Sandel: It was interesting for me listening to the Malcolm Gladwell podcast because he talked about the ethics piece. I’ve repeated this on the podcast before, like this is an experiment that could never be done again. The final point that Malcolm Gladwell came to was, why shouldn’t it be done again when you actually hear all the participants takeaways from doing it? Every one of them, when asked “Would you do this again?”, was like, “I would do this in a heartbeat” and talking about how much of a positive impact it had had on their lives.

So I would love to get your thoughts on that, from an ethics standpoint. What do you think about this?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: That’s a great question. I think that one of the biggest challenges is that we have historically experimented on vulnerable populations. When human studies have been done, they’ve been done on folks who either – sometimes they didn’t know they were being experimented on, sometimes they were being experimented on in order to get some sort of reward in an otherwise really difficult situation, like a prisoner in a jail being experimented on.

I think it is really difficult to say “Okay, scientists, you had a crack at this; you did a lousy job of getting real consent from folks before, but you’re going to get it right this time.” That’s really hard. I do hear that the men who were part of the starvation experiment are proud of their participation, they feel like they contributed to knowledge – and we heard in that podcast about the folks who volunteered to be infected with Covid-19 in order to take part in experimental treatments. There are people who are willing give their bodies, give their lives, for the greater good, and that’s very honourable. I respect that decision.

It’s really hard for me to say, “That’s okay, we should let scientists decide to do that again” when the errors, all the things that have been done in the name of science to vulnerable populations, still have happened. I hope they are not still happening. But that’s where I see the challenge. I respect that there are folks who would be willing to subject themselves to great risk in order to benefit the world, and there are people who do that in their professional lives every day. There are firefighters and police officers and folks who put their lives on the line to help other people, and I respect that. Maybe subjecting yourself to experiments is a little bit like the role of being a firefighter; you’re going to go into that burning building and save someone else.

Chris Sandel: Yeah. It was interesting in terms of with the conscientious objectors; in a sense – and I think some of them directly said this – “I wanted to have an honourable explanation for what I did during the war because of how it was seen to be a conscientious objector.” So is the person who is doing this experiment doing it purely because they are wanting to further science and help, or is there some part of them that is like, “I need a better explanation for why I chose not to fight”?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: Yeah. There were folks who said, “You’re a conscientious objector because you’re a coward. You’re afraid.” Participating in the kinds of experiments that COs participated in, including heat trials and cold trials and all the other ones aside from the starvation experiment I think were a way that they could say, “Look, I’m not afraid of pain. I’m not afraid of danger. I’m morally opposed to taking another person’s life, but I am not a coward.” What are all the motivations? Yeah, that’s pretty hard to tease out.

Chris Sandel: As one of the people in the podcast then said, he did such a good job with doing this experiment that to redo it today, yes, we would have some extra data because of the advancements in science, but in a lot of ways this was a pretty perfect experiment for getting the information that we wanted to get.

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: Yes. I will note that in addition to more kinds of data, there was very little diversity in the population, it being 36 white men in the ages of 20 to 30, approximately, something like that. How do these nutrition things affect women? How do they affect people who are outside of that narrow range of ages? There’s a sample issue, I would say, as well. But yeah, I do remember that there was one person who was like, “Yeah, that’s a great experiment. I would just do it again with our better data.” I think they may have also said broaden the population, because it was a fairly narrow range. [laughs]

Chris Sandel: Yes, definitely.

00:25:51

Do you know what your dad’s eating was like before the experiment? You can talk about prior to the war if that was also having an impact on his eating. What was it like growing up, what was his relationship with food, if you know?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: Basically the only story of food from before the war that I know is he grew up in – the Church of the Brethren is a religious group, but they’re part of a community that is also sometimes called Pennsylvania Dutch. They’re folks in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, whose ancestors came there from Germany, and in that tradition, my father would say there was pie at every meal. His mom was making pies all the time, and there would be fresh pie for dinner and then leftover pie as part of breakfast and lunch, and then in the afternoon she’d be making more pies for dinner and the next day.

So pie at every meal was something that he has definitely talked about for the time when he was living at home. When he showed up to the starvation experiment, I think he weighed 165 pounds and he was 5’10”, and then during the standardization period when they were doing a bunch of baseline testing and exercise and standardized meals, he went down to 150 pounds. He described that as being very lean, muscular. He was in very good shape at that point before they started cutting the food back.

00:27:38

Chris Sandel: What stories did he tell you about during the experiment? Do you remember him commenting about any particulars with it?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: He talked about eating everything off of the plate and licking the plate when he was done. He knew the story that we heard about in the Malcolm Gladwell podcast of the participant who chopped off fingers, but I don’t think my dad knew the whole extent of it. He knew the man eventually came back. But I remember him telling me that that had happened.

He shared that when he was hungry, he didn’t care about anything else other than food. I think he’s quoted in other things – and he said this to me – “I didn’t care about the kissing scenes in the movie. I wanted to see the parts where they were eating.” Or seeing other people eat in the window of a restaurant or café would be challenging to watch. He didn’t think about anything else.

And that meant that if you had a population of people who were hungry, it didn’t really matter if you had a really great political idea or you wanted them to rebuild something; they weren’t going to be ready to do that until you’d taken care of them being hungry. You had to feed people first before you took care of other things. Those were some pieces I remember him talking about.

Chris Sandel: That final one you mentioned was also something that Keys had talked about as well. I think the first time there was an uprising of any sort was during the point when they were starting to be fed more food. Prior to that, they went along blindly with whatever was asked of them.

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: Right. When they started to get food, they started to organise into a collective of the subjects and advocating for themselves as having some more rights.

Chris Sandel: Were there any specific troubles that he had during the experiment? I know it was tough, but was there anything specific with him?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: I think he tried – he was not a smoker, other than I think he tried smoking a pipe for a while during the experiment to see if that would help him to not feel so hungry. I don’t think that worked. He talked about watering down his coffee and then getting oedema. That was another picture that I remember distinctly. His ankles were just totally swollen up with fluid that he was retaining.

Some of their weights later on, probably an awful lot of it was extra water they were carrying because they were drinking a lot of water to make their stomach feel full. They weren’t restricted on how much water they could drink, as far as I know.

Chris Sandel: Do you know if he was someone who was losing weight easily or not? Because I think that was a big thing that’s been talked about as part of this with the participants. There would be a board that would tell you what your rations were going to be for the week, and your rations would be based on how either quickly or slowly you were losing weight. Do you know how he was with that?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: I don’t remember details. They separated folks into different categories when they were getting rehabilitated on how much fat and protein and so forth. As the weight was going down, I don’t remember whether he was always getting his rations cut or not. That might be present in some of the other interview transcripts. He didn’t talk a lot to me about watching whether somebody else was getting more bread than him.

He did talk about they had to do a fitness test regularly of running on a treadmill for a certain amount of time at a very high pace, and he was athletic enough that he could run for the whole time during all of the standardization time. There were a couple of guys who were fit enough to run. It was running for 10 minutes at a really quick pace. But pretty soon after they started limiting their diet, he wasn’t able to do that anymore.

He talked about feeling like he was really old. He imagined that what he felt like when he was at the low weight was what it would be like when he was 90 years old, because he would move so slowly and couldn’t get up if he sat down and felt cold all the time and all those things. He felt like he was being prematurely aged.

Chris Sandel: I know different people collected cookbooks and really got in that area. Was that something for him during the experiment?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: He didn’t talk about collecting cookbooks. I think he read magazines and looked at the food ads and the food pictures in magazines. But as far as I know, he didn’t become a cookbook collector.

It also did not drive him to become somebody who liked to cook after the experiment. For me, growing up, my mom did all of the cooking. My dad didn’t go do the grill, he didn’t do any of those things. The only times he made food were he would make his own lunch to take to work, so he’d make a sandwich for himself and take it to work, or if my mom was away, he would go to the store and get some hamburger and we’d have hamburgers fried in the frying pan on bread for dinner for a couple of nights. [laughs] So he was not a gourmet – food was necessary; he was going to eat it, he was going to make sure it was there, but he was not a gourmand. He was not somebody who saw food as something to bring him a bunch of enjoyment. It was a fuel to make him able to do what he needed to do.

00:34:16

Chris Sandel: What about his mental state during the experiment? Did he talk about this part of it? I know they had to keep doing the – I’m blanking on the name of the test.

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: MMPI.

Chris Sandel: The MMPI, yes.

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. He did tell me about having to take that test over and over again, which at that point was done by sorting cards into stacks of “Do you agree with the statement or disagree with the statement?” He said they were weird statements. They came across to him as very weird statements, some of them, like “I think about killing myself” or things about their bowel movements. He’s like, “I don’t know why they were asking those questions”, but they were in the MMPI at that point. Which I think was very early days for that test, which has gone through a bunch of iterations since then.

Talking about his emotions and his mental state was not something my dad was very good at, so I don’t feel like I have a good window into what he was feeling, other than occasionally things that he wrote or that he might’ve said in an interview to somebody else. But that was not part of his general interactions with me when I was a kid growing up.

00:35:37

Chris Sandel: After the semi-starvation part of the experiment, there was then a phase where the participants were split into different groups and they were on different amounts of calories. Do you know if he was in one of the higher groups or the lower groups or what happened at that point in the experiment?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: I can consult the document that he wrote, his own autobiography. He did write about that, so let me see if I – let’s see. “I was given 3200 calories a day.” He had the lower amount of protein, and he did not get vitamins. He was taking a placebo pill. And then he says, “After six weeks, everyone was raised 1000 calories.” So six weeks into that, he went to 4200 calories a day. Three months of rehabilitation brought him up from I think about 115 pounds to 135 pounds. He was not back to his 150.

So he was at the highest number of calories a day at the beginning of the rehabilitation period, because he said at the start of rehabilitation the lowest number was 2000 calories. Which is hardly more than they were getting – they were getting 1600 calories during the starvation period.

Chris Sandel: After that rehabilitation period, there were 12 volunteers that stayed on for a further eight weeks. As part of that, was your dad one of those who stayed on?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: Yes, I’m looking at that part. He said during that period, they fed them 6500 calories a day. And it continued to be starches, like a lot of potatoes and bread and cabbage and stuff like that. At the end of that further three months, he’d gone all the way up to 180 pounds, so he was well over his initial weight showing up even before standardization. He showed up at 165, went down to 150 in standardization, went all the way down to 113-114, and then six months of almost unlimited eating and he was 180 pounds.

Chris Sandel: Do you know how long it took for him to recover after the experiment from a physical standpoint, where he felt like he was back in his original body? And I don’t necessarily mean just from a weight perspective, but “I feel like all the repair that needed to take place has now taken place.”

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: He talked about it as being a couple of years more. Looking at this document reminded me that another one of the lasting psychological things that he describes is feeling like it made him more self-centred. He was like, “Well, I just did something really hard, so I deserve other people to take care of me.” He reported that his mom loaned him some money for a bus ticket somewhere, and when she asked for it back, he said, “I don’t have it because I did the bus ticket and then when I earned back more money, instead of paying you back, I used it to buy a bicycle.” He felt like that was evidence of him being self-centred afterwards. He didn’t honour that commitment to his mom to pay her back what was supposed to have been a loan.

Chris Sandel: And this was then a permanent trait, a lifelong trait? Or that was just during the acute recovery stage?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: That’s hard to say. Of course, I didn’t know him before this, but I would say that he tended to think of himself before others most of the rest of his life in some ways. He volunteered to do certain things, but I would not say he was especially good at taking another person’s perspective, and not always super good at recognising the ways that his actions that seemed to make sense to him could be seen as indifferent by somebody else, or even potentially harmful to somebody else.

So I would say that it lasted – it was at least some part of him, but how much that was in existence before the starvation experiment, I of course don’t know.

00:40:20

Chris Sandel: What was his eating like after the experiment? Obviously there was the stretch where it was very much about the recovery, but then as you knew him, when you were a kid and then up until when he passed away.

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: Main things are if something was on the plate at dinner, he was going to eat it all. His plate would be empty when he was done. I can’t think of things that he would say, “I don’t like that, I don’t want to eat it.” He would basically eat whatever was provided to him.

I was talking to my older brother last week and he said, “Don’t you remember, he would always eat the garnish at a restaurant?” There was a period in the ’70s or earlier where things would come with a little sprig of parsley to decorate the plate, he would probably eat the parsley. Or there’d be a decorative little slice of orange maybe on the side, and he would eat the slice of orange. He would not eat the orange peel; he would leave the orange peel. But if it was edible and it was on the plate, he was going to eat it, even if everybody else would see that was a decoration, that was just the garnish.

He had an expectation that there was bread at every dinner on the table. Whatever you were having for dinner – pasta, soup, didn’t matter – he expected that there would be some sliced bread and butter at the table. Which was in some ways a tool. It was a way to put things on the fork.

So he saw food as fuel, he was going to eat it, and refusing something didn’t ever seem to be an option for him. He wasn’t going to say “No, thank you.”

Chris Sandel: You mentioned last time when we chatted about there was a time when ants got into his sandwich and he was like, “That’s fine. I’m going to continue to eat this sandwich because this is what I’ve got.”

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: Yep. Later in his life he was a general contractor and would be out on jobsites, building things, and at that jobsite, ants got into his lunch and it was like, “Well, this is my lunch for today. I’ll either be hungry or I can eat this with a few ants in it.” [laughs] So he brushed the ones off that he could get off the outside and ate the rest of it.

Chris Sandel: After the experiment was over, did he keep in contact with any of the other participants? I know we’re going back a long time and there was a lot going on and people were scattered all over the globe because a lot of the relief work, but was he in contact with any of them?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: I am not aware. Other than a couple of times when there were communications around reunion sort of events, I’m not aware of him keeping in contact. He had grown up and lived in the Midwest, in Indiana and Michigan, and he went to college in Indiana, and then after the war and after some relief work that he did with his first wife, he and his first wife moved to California. So he was far away from where most of those folks were. I don’t know of him having much contact with them afterwards.

There were a couple reunion kind of events, and I’m not sure of how much participation. I know he had some phone call kinds of things, but I don’t recall how many of those reunion events he attended.

00:44:01

Chris Sandel: What did he do after the war? How did he spend his time?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: The work in Florida was after the war was over but before the Civilian Public Service was disbanded. So in the same way that not everybody was released from their military service right after V-J Day, they didn’t immediately shut down all of the CPS things. So he finished that. When he was released from that, he went back to Manchester College and finished his degree. He studied history. And he got married.

He and his wife at the time – not my mother, but his wife Dottie – decided that they wanted to do relief work, and they applied to several of the churches that were doing relief work in Europe. The first one that responded positively to their application was the Quakers; the American Friends Service Committee is what it was called. So he and Dottie went to Europe a couple of times for nine months to year-long periods.

First they were in Poland, and he drove a large truck to carry building supplies or carry away rubble from building sites for folks who were rebuilding their homes after the war. So they were in various communities around Poland for a while, until it became impossible for Westerners to be in Poland as the Iron Curtain came down. After Poland essentially kicked out everybody from the West, then they went to Greece for a while; they worked in Germany. Just moved to different places where they could do similar sorts of work.

When all of that period was done, he moved to California and was a high school teacher in a few communities around Northern California and eventually became principal of a Quaker boarding high school in Northern California. This Quaker school was in rural Northern California, and that is where he met the woman who was my mother. Family relationships changed around there, and then basically after the time at the high school ended, he got a master’s degree in political science and wasn’t ever a classroom teacher again – he said because it was too hard to get a job when he had a master’s degree and many years of experience. I also think he wasn’t especially good as an employee of other folks; he tended to have his own way to do things.

So then he got a contractor’s license and was a homebuilder for the rest of his professional life. All the time that I was growing up, he built houses for a living.

Chris Sandel: Were there any lasting negative effects that you think the experiment had on your dad?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: Hmm. If the fact or the idea of him being more self-centred is valid, which he said was true at least for a while afterwards, I would say that’s probably a lasting negative effect.

Physically, I don’t know of any. He remained very healthy into his later years. He was physically active and building things into his eighties. I don’t think he was very careful – my mom was not cooking to avoid cholesterol in the way she might’ve done. I mean, she did care about health; she bought whole grains and things like that. But there was a lot of butter in the house. His exercise all came from his work. He did have a valve stenosis and a heart bypass surgery when he was around 80, which is fairly late. He wasn’t a young man when that happened, but he did have a heart valve replacement.

Then what eventually led to his death was a glial brain tumour, glioblastoma, which I don’t think was in any way related to the starvation experiment or anything. I don’t think we know why those happen. And he passed away in 2012. He was 88.

00:48:41

Chris Sandel: Do you think it had a positive effect on him? Is there anything you can think of where you’re like, “I think he took this from it”?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: I think he was proud of it. Later in his life, I think he was much more open to talking about it. I was a college professor for a while; I am no longer, but I did invite him to come and talk to one of my classes about his experiences as a conscientious objector, and I think he enjoyed that and enjoyed speaking to young folks about it.

I’m not sure how well-known the history of conscientious objection is in the United States by the general public. I know it well from my personal experience. Some folks have a sense of COs because of the Vietnam War, but there was another group of folks who avoided service in the Vietnam War by leaving the country or by feigning mental illness or doing other things. So I think sometimes folks don’t have a very clear understanding of that. So after he didn’t have to worry about his livelihood, he didn’t have to worry about being fired for talking about it, he enjoyed sharing that story.

I think he was proud to have contributed to knowledge in the world. He was interested to know that the way people came to find out about it much later was in understanding eating disorders. There was a fairly long period where nobody had any conversation – there wasn’t any national conversation about the starvation experiment. But then a couple of books have been written, and I think it had a life in the academy that he didn’t know about. He didn’t know until folks who were having challenges with disordered eating would say, “Oh, I heard about this study” and he would be like, “Yeah, that was me.” [laughs]

Chris Sandel: It is such an important study in terms of what we know about the body and the mind as part of starvation. It has been so valuable for eating disorders and understanding that and for the work that I do with clients. It’s so useful. So I’m glad to hear that he’d realised that before he passed away, he’d known that it was being put to good use.

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: Yeah. He did recognise the difference between his situation, where he went into the experiment knowing that there was going to be a day when it was going to be over, and that he would get enough to eat – he recognised that that was different than the situation for someone who the experiment was originally designed to help, which is folks who were malnourished because of the war, or folks who were malnourished from some other natural disaster or something like that. They don’t know that there’s a date certain when that will be over.

I think he also understood that his situation was different than that of someone who’s dealing with disordered eating, where they also don’t know there’s an end date to it. They may feel like there might not be an end date. And it was being done to him in a way that’s a little different.

Chris Sandel: For sure.

00:52:29

It was between 2003 and 2004 that they got 18 of the original participants and interviewed them and left an oral history of their experiences. This was what the Revisionist History podcast was based on, those interviews. Your dad was one of the people who was interviewed as part of that. Do you remember at that time him telling you about his experience of being interviewed or telling you that he was being interviewed?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: I knew that it was happening but not really any details about it. For me, at that moment, I was in my graduate programme and getting a PhD in science education, so I was pretty busy with that at that particular moment. Then for his health, that was also the time that he had the heart surgery to do the valve replacement and a bypass. I only realised the coincidence of that when I listened to the recording and saw the transcript and heard him say, “Oh yeah, I’m home now because I’m recovering from the surgery” to realise that they were that close together.

So I knew that the interview had happened; I also knew that he had talked to some other folks who did some writing about the starvation experiment. But I did not know the details and I didn’t know that the recordings were available in the Library of Congress until I heard the Revisionist History podcast. It was the first time – it was a surprise to me in listening to the podcast to be like, oh, that’s my dad’s voice. They did not identify him by name in the podcast, but I recognised his voice. Like, that’s interesting.

I have reached out to Revisionist History and I’ve had a conversation with one of the producers. They may possibly be doing a follow-up show; they haven’t decided yet. But the producer talked to me and talked to another relation that had reached out to them since the podcast had come out.

Chris Sandel: How was it for you either listening to that recording with your dad or reading the transcripts? Did it bring up anything for you? Was there new information? What happened?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: Hearing his voice, it sounded – I could recognise it, but it didn’t sound like my memory of him. It turns out, I think, that part of that is because it was shortly after having that surgery, so he was recovering from major surgery. I’m sure he wasn’t taking the kind of deep breaths that he usually did. He was an amateur singer all of his life, so he knew how to breathe to support his voice, and that recording doesn’t sound like that to me. It was helpful to me to know that piece.

There were some details that were new. I’ve also been doing some of my own reading about the conscientious objectors and the Civilian Public Service, so now I’m having a little bit of difficulty separating out which pieces of information came from where. But he tells stories in there that I had heard, but sometimes also with a little more detail or a different version. Like the story of eating all the food and getting on the bus and being sick on the bus. He hadn’t told me that one in as much detail before, so I got some more sense of how that had all happened.

Maybe he’s thinking about that selfishness where he said, “I was sick on the bus and then I just got off and left. Oh well, somebody else had to clean it up. I felt a little sorry for the guy who had to clean it up”, but he didn’t stick around to try to solve the problem. He just made tracks. [laughs] It’s like, okay.

Chris Sandel: How is it for you with all of this renewed interest in the experiment? Obviously, your father has passed away. I don’t know if this is then bringing up thoughts or emotions as part of that.

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: I would say that before this renewed interest came up, more of my thinking about my dad had been – I am a father. I have two kids, one 12 and one 10, so I have thought a lot recently about ways I am parenting that are different than how my parents parented me, ways that I am being a father to my son that’s very different than how my father was with me.

So I guess I’ve been thinking a lot more about the ways that I wanted to be different from my father; hearing the podcast, thinking about these things, reading these things, I’m reminded of the things he did that I’m proud of and ways that taking a principled stance and putting himself in harm’s way in light of that principled stance is something that I do respect and that I’m proud of him for.

I think I’m a little more – it is a piece of information of my family history that I don’t always share in new settings because I don’t know how well folks will respond to the idea of conscientious objection as opposed to military service. There are some communities where there’s a lot of respect for military service and community service in that regard, and I don’t know how it would be heard or taken to hear that my family’s history is on the other side of that as CO and community service in a very different way.

Chris Sandel: Jacob, this has been awesome to chat with you and hear about your dad as part of the Minnesota Starvation Experiment. Is there anything else that I haven’t asked or we haven’t covered that you think is relevant or you want to mention?

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: My experience of what he was like – I was born in 1970, so that was 25 years after the experiment was over, approximately. My father had five other kids who are 12 to 20 years older than me, so his oldest son was born just a few years after the starvation experiment. I’ve talked with him a little bit. I’ve talked with those half-siblings of mine a little bit. Dan reminded me of the garnish experience, and that stuck out for him.

But I do want to acknowledge that they may have had different kinds of experiences with what he was like in closer proximity to the experiment and when he was more actively hiding this, because they were children when he was in roles where he didn’t feel like he could share it. So my experience is limited by the time period that I knew my father, and there are other kids of his who may have had a different experience.

I have good friends who have a child who has dealt with disordered eating, so they learned about the starvation experiment through that. So I’ve talked to them about it some. Anything that can help folks deal with the challenge that that is and help them to recover, I’m really pleased that my dad’s experience has helped with that, because that’s a very scary thing to imagine as a parent, to have a child dealing with that illness.

Chris Sandel: Definitely. Thank you for doing this. I really appreciate it.

Jacob Clark Blickenstaff: You’re welcome.

Chris Sandel: So that was my conversation with Jacob. I’m so glad that he reached out and we got to chat. It is such an important study and an important part of history.

That is it for this week’s show. I’ll be back next week with another episode. Until then, take care and I will catch you soon.

Thanks so much for joining this week. Have some feedback you’d like to share? Leave a note in the comment section below!

If you enjoyed this episode, please share it using the social media buttons you see on this page.

Also, please leave an honest review for The Real Health Radio Podcast on Apple Podcasts! Ratings and reviews are extremely helpful and greatly appreciated! They do matter in the rankings of the show, and we read each and every one of them.

Share

Facebook

Twitter